Cynthia Pearl Maus and regions in the Disciples of Christ, pt. 2

Our Disciples of Christ story embodied in one remarkable person

In many ways, the personal story of Cynthia Pearl Maus sums up the social circumstances of the Disciples of Christ in our first century.

She was born in 1878 to a farming family, her father a wounded veteran of the Civil War, which then took on homesteading in Colorado, living in a sod house for two years before crop failures drove them back to the Midwest where her parents worked a mix of trades and manual labor as they sought middle-class respectability for their children.

R.D. Maus had a veteran’s pension which clearly kept the wolf from the door at many times, not enough to live on but enough to allow the family to survive under some truly appalling conditions at times. You can read about all this in more detail in Cynthia Pearl Maus’s autobiography “Time to Remember,” written at age 84 and finally published in 1964: https://archive.org/details/timetoremember0000unse_k5t1/

You will find some familiar stories of pioneer hardship; you will also, it must be said, encounter some chilling racism which might cause you to set your reading aside for a moment or two to collect yourself. I fear it represents an all too common for the time and casually offered racist perspective about people of color, in a few passages which are painful to read but important to be aware of. Maus can come across, not inaccurately, as a social progressive in some chapters, and in others as a conservative of the most backwards and troglodytic stripe. In any case, you’ve been warned.

There are also elements of her education which sound familiar, and then jump to a statement of progress which sounds odd today, but historically is again very much of her time. Maus attends a fairly typical series of grades through high school, finally in Parsons, Kansas, but then the picture shifts. Her senior year of high school is a special preparatory program through a “Normal School” for prospective teachers, and immediately she leaves with her high school diploma to teach grade school for the next five years. Yes, she’s a schoolteacher immediately after leaving high school. In the 1890s that was still common in much of the country, especially in rural areas.

During those five years, she shows the drive already evident in her character in taking summer school courses each summer, while also going to work weekends on the Chautauqua and Lyceum circuits, which were national and regional programs of traveling speakers, intended for a mix of entertainment and moral uplift. Keep in mind, this is the late 1890s into the first years after 1900, and radio isn’t even on offer yet. Maus was clearly a gifted public speaker in her youth, and she honed those gifts on the speaking circuit across the Midwest. How she did both I do not know, but she clearly also got comfortable in this time with arduous and uncomfortable train travel, which would stand her in good stead in the 1920s as she launched the Young Adult Conference movement for the Disciples of Christ.

Having done summer coursework for five years, she moved with her now semi-retired parents to Evanston, Illinois, and completed a bachelor’s degree in Speech in just two years at Northwestern University. Along with a few business courses in St. Louis, this would be the sum total of the formal education of this remarkable woman, who would define and shape education and educational aspirations for our movement for decades to come.

Maus was always very proud of being a Northwestern alumni. Of her two years there, she said “There, for the first time in my life, I had the privilege of coming into contact with young men and women from all sections of the United States, as well as students from many foreign countries. It was in a very real sense the most democratizing experience of my life. Whatever midwestern personality limitations I may have brought to the university were to a large degree lost in the rich fellowship of sharing viewpoints with young people from everywhere.” (TtR, pg. 76)

It’s also worth noting it was there that “The largest single contribution that Northwestern University made to my life was in developing appreciation for literature in relation to the art of living richly. To me the individual who never reads, who has little appreciation of or acquaintance with the world’s great literature, is always tragic, and especially if and when that person purports to be educated. Yet you will find them on every hand: men and women who are graduates of some of our leading colleges and universities, but who, at middle life if not earlier, are dried up and barren so far as their appreciation of or acquaintance with literature is concerned.” (pg. 82)

Maus would go on to make it clear that formal education, a college degree alone, was no indication in her books of a truly cultured and educated individual, and that many without such schooling in her experience had more learning out of their reading and exposure to culture than those presumed to have it from their credentials. This would become part of the agenda she would bring to her career following her somewhat forced and early retirement from the United Christian Missionary Society (UCMS), or what we’d call today the general offices of the Disciples of Christ. It’s also a perspective you don’t have to go far to find among today’s Disciples.

After her graduation in 1905, she and her parents moved back to Kansas, and Maus frankly describes her challenges finding a full-time teaching position, but between tutoring, substituting, and her Lyceum speaking on weekends, she was making a reasonable living albeit while living with her parents. By this time her siblings had all grown and mostly married; one older sister was now living in St. Louis, and in the summer of 1908 she went for a visit and essentially stayed. She saw an ad for a business manager position with a company, talked her way into it, took night courses in Pittman shorthand, and joined a local Disciples church on Hamilton Avenue*. There she was quickly enlisted to help and ultimately run the Sunday school program, and through that role got involved in city-wide Christian education efforts and missionary promotional programs.

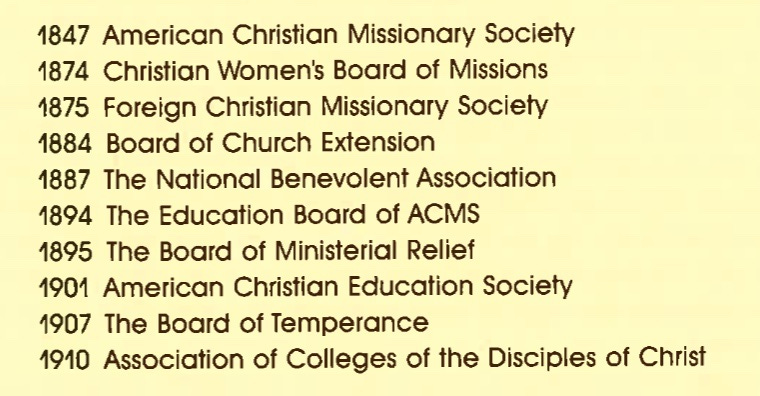

In 1910, the Disciples of Christ would be as “centered” in St. Louis as they were in Cincinnati; Indianapolis would not become a center of gravity for Disciples institutions until 1928. In her career with elements of the Disciples of Christ, from Christian Board of Publication (CBP) to the Bible School Department of the American Christian Missionary Society (ACMS) to what became the more-unified UCMS, she would move from St. Louis to Cincinnati to St. Louis again and only at the end of her tenure in church work to Indianapolis, from 1928 to her “retirement” in 1931. It was a time of much innovation and ferment for what we now consider “general units” of the church, most of which began informally and with a local impetus before becoming national, and later general initiatives of the wider church, and the “inevitability” of Indianapolis was only apparent after 1928, with some units like CBP, NBA, and what would become HELM never leaving St. Louis even when other groups moved to Indianapolis. CBP was incorporated in 1911 by R.A. Long (another much neglected figure in our history as a movement), but had roots in St. Louis back to 1874 and J.H. Garrison’s Christian Publishing Company, a privately owned vehicle for a periodical edited by Garrison which was purchased by Long and incorporated as, in his intention, a denominational publishing house; it continues in the St. Louis area today as Chalice Press and Chalice Media Group, “affiliated with” the Disciples of Christ.

As you can see above, our Disciples’ “alphabet soup” was at high simmer come 1910, heading for a boil in 1920 with the formation of the UCMS merging a number (but not all!) of those groups into a single organization . . . and triggering a level of resistance from groups focused in Cincinnati (around Standard Publishing, founded in 1866) to a unified missions organization for Disciples, which would ultimately result in a full break by 1968 and Restructure. All of that is to come, but the stresses and tensions around who would be “in charge,” and where missions money would be sent from local congregations, were all beginning to be felt in these years when Cynthia Pearl Maus was coming into her own as a church leader.

Knowledge of shorthand got Maus into CBP as a secretary, but she quickly became an editor for the new approach of “graded materials” for Sunday school classes, and with her public speaking skills combined with teaching experience, she became a key player in the traveling “School of Methods” program led by the Bible School Department of the ACMS, which we would call the Christian Education program today. The “School of Methods” was related in history and approach to the Chautauqua and Lyceum models of voluntary education for untrained (and often relatively uneducated) teachers in church schools, all of which Maus was well familiar with, and in which she could quickly become a leader.

Between 1913 and 1914 her role, by her own telling, was blurred between CBP and the ACMS’s Bible School Department, and her transition was complete as she began to direct the new program of “Week-end Young People’s Conferences,” to do for young adults what the “School of Methods” had done for teachers. I told that story in my last post, linked here:

Cynthia Pearl Maus and regions in the Disciples of Christ, pt. 1

“Looking backward over more than two decades of service, one of the contributions in which, as the Pioneer Young People's Superintendent, I have had the greatest joy was the initiating of the seven-day summer Young People's Conference movement among the Disciples of Christ.”

There I also sketched how her idea for a week-long Young People’s Conference came to fruition in the summer of 1920, neatly overlapping with the formal establishment of the UCMS out of the ACMS and an assortment of the national boards brought together from a variety of locations in Midwestern cities . . . but initially in Cincinnati, then to St. Louis at the strong encouragement of philanthropist R.A. Long (he who incorporated the CBP in 1911), and again only to Indianapolis in 1928 as the College of Missions buildings in Irvington came open as Butler University moved north to Fairview Park.

The summer Young People’s Conferences, ironically, became a point of relative stability in the definite confusion of church institution boards merging and reforming, seven in sum if you include the Disciples’ Christian Endeavor Board . . . and you should, because in no small part I suspect the impetus behind supporting the rapid spread of the UCMS Bible School Department’s program was how the Christian Endeavor organization, nationally, was an independent group, an early parachurch organization akin to what we know of today as Cru or Intervarsity or Fellowship of Christian Athletes. They had their own funds and officers and were entirely independent: the Young People’s Conferences were unambiguously OURS.

The challenge our hero runs into almost immediately, as “Pioneer Young People’s Superintendent” (let’s note that in “Time to Remember” she notes her title of pre-eminence not less than 25 times, but it’s true; to be fair, she was from 1914 “the first fulltime young people’s superintendent employed by any Protestant Church on the North American continent”) is that in 1921 the new UCMS was already . . . broke.

Her direct supervisor and the reason for her hiring, Dr. Robert M. Hopkins, would ultimately leave the Bible School Department for the World’s Sunday School Association (but would later return to serve as president of the UCMS), as a funding crisis growing out of the unexpected failure of the Interchurch World Movement resulted in drastic budget cuts across the newly established UCMS structure.

One result of this was that in order to continue holding Young People’s Conference events, let alone to expand them from the original six, the youth themselves were asked to put up a sort of “performance bond” raised from among themselves to allow rentals of sites and the purchase of material. The records are a bit murky, but the bottom line is that the UCMS office did not hold onto control of the program, but directly turned the future of the program over to local supporters, and in fairness allowed both Cynthia Pearl Maus to travel as an initiator, but also for any sponsor — a Disciples college, a Chautauqua campground (remember, no Disciples institution owned a camp or conference center at this point), or a state missionary society — to use the model freely for themselves. Most of them turned to Maus for the initial week’s program, but like Paul in Asia Minor, she moved on leaving the local program to direct its own future.

Those choices, however made, would be significant on a number of levels for our common life as Disciples of Christ, especially in the state societies, which we know today as regions.

Before I close this second part, and turn to a conclusion in part three (and a poignant coda), I should note that Maus wrote a book in 1919, “Youth and the Church” which was in her words “the first book published by any publishing company on the organization and administration of the Youth Division of the Church-school, and as such was received with unusual favor” (pg. 144). She wrote, as the Young People’s Conference movement grew, two more works, “Youth Organized for Religious Education” and “Teaching the Youth of the Church” in 1924 and 1925 — and it’s no coincidence that while her first work was, as you can see below, published by “The Standard Publishing Company,” her latter two came out through CBP’s “The Bethany Press.” They together establish her as a preeminent voice in youth development across Protestant church life, in contrast to “children” as a separate subject for education from adults, and the publication history of these three interconnected books marks the gathering tensions between institutions which would lead to splits on multiple levels, including how the competing models of Youth Conference versus Christian Service Camp would help define the divisions between independents and cooperatives in the coming Disciples of Christ schism.

Youth Conferences, which by the end of the 1930s would become Christian Youth Fellowship Conferences, or CYF programming, helped to shape and define and in some cases literally build the superstructure of today’s Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), especially when it comes to the transformation of state missionary societies into regions, as we know our middle judicatory life in regions today.

[part 3 coming soon!]

___

*This congregation would later move out to the St. Louis suburbs in Creve Coeur, and closed in 2013.

That’s gonna take some work. Long was quite a character, but kept his cards close to the vest. I have indications & suspicions, but hard data is tough to find. Long, Phillips (Sr. & Jr.), and Rockefeller Jr. danced quite a number round and round (or their proxies did) between 1892 & 1931. C.R. Scoville being one such intermediary…

A hidden in plain sight cog in these works: the Interchurch World Movement 1919-1921. It’s worth some attention. Also the Men and Religion Forward Movement of 1911-1912, which caused Long to launch the Men and Millions Movement in 1913 (proto-DMF). Efficiency & vertical integration were what Long & Rockefeller had in common, and what Phillips loathed; it splashed into religion in a big way.

I’m dying for 10,000 words on the College of Missions and RA Long.