If you’ve ever cracked a rib or broken a toe, you know the problem.

They don’t heal well because you have to keep using them. A boot might help, but generally a broken toe is something you’re told “keep off of it as much as you can” but walking means you flex and work the darn thing even without putting weight on it; a rib would heal faster, witty doctors tell you, if you’d just stop breathing for two or three days. But life goes on, even if healing is slow.

Dad died five years ago today. It still hurts. No real problem, it just never quite has healed.

The cliches are “you never get over the death of a parent” and “you will always mourn those you loved” and so on. I get all that. But it’s much more complicated, given that he died on March 12, 2020.

That week broke me. I started healing March 24th, just twelve days later, for reasons that would be a different story altogether, but the reality is I still have a fair amount of pain because I keep flexing and bending and stressing the break point.

One cause of the break is that Dad’s death was the twelfth I was involved in since Christmas Eve, not twelve weeks earlier. Three of those were of major figures in the congregation where I was minister, whose deaths left a deep and wide shadow on the church; the call about Dad’s passing came during the break in calling hours of the third of those three. I went back in after fielding the call, and making three more to family members, then finished the evening at the funeral home. We held the service the next day, then I drove to my sister’s so we could catch a plane to Texas the day after that. But it did feel as if a hammer had tapped at me twelve times until the last blow cracked me through and through.

Another, I’m sure you’ve put together, is that it was March 12, 2020. The night before we all heard through the media about Tom Hanks getting this new thing called “COVID-19” and a basketball game was cancelled in mid-play when a player tested positive for this “novel coronavirus.” The running joke in our family since March 12, 2020 has been that Dad, who since about age 3 had been profoundly deaf, wearing a hearing aid but getting by as much by lip-reading as by hearing technology, got up in the morning, fetched his newspaper, made a pot of coffee, took a cup to the easy chair, turned on TODAY, heard about what was coming with this whole COVID thing, and said “Nope” and died right there, coffee unfinished.

On our trip down to the Rio Grande Valley (where my parents had been spending half the year since 2005), my sister and I were fielding news reports about impending closures and restrictions and even state borders possibly closing (that last never happened, but they were discussed all the way until I got back up to Indiana a few weeks later). We brainstormed “what ifs” and scenarios for how we’d handle the service in Texas at Pharr South, how we’d get Mom home, and what to do for a memorial service when back in Valparaiso (which turned out to be late in July, outdoors).

Meanwhile, the associate minister back at the church was fielding all sorts of flack over whether they should or shouldn’t open on Sunday; this didn’t get better in the next few weeks. She handled it all about as well as anyone could have under the circumstances, as did many clergy and church leaders. She mastered some online skills and offered worship experiences that way while I was busy a few states away.

Not because of her, but around the situation in general, I began to get angry messages. Emails, Facebook comments and messages, Twitter direct messages, even one voicemail on my phone. Messages challenging whether church should meet in person, or not. Monday of that fateful week, March 9th, there had been a leadership meeting that should have told me what was coming. Word of an infectious disease spread was already in the air, even if the word “pandemic” wasn’t quite in common usage yet; I prepared for that meeting in between visits to the hospital’s hospice unit for what would be my Friday funeral before flying south. What I brought to that meeting was perhaps not my best work, but it didn’t matter, because it was made clear to me they didn’t want to hear it. I got an hour’s worth of tales about how government and vaccines and precautions were always out of line and excessive — remember, this is BEFORE any pandemic closures or state mandates anywhere, let alone the minimal ones in Ohio — and to take my suggested cautions and precautions and set them aside.

I also learned, to my surprise, that a number of people had for years been unhappy I would mention each fall in the newsletter and usually as an aside in the announcements on Sunday that it was time to get your flu shot. They didn’t like it, thought I shouldn’t say it as a minister, and it bothered them. Again, this is BEFORE the pandemic caught fire and led to closures, controversial or not. This was on March 9th. I had no idea. No one had ever mentioned it; I didn’t put much weight on it, but it was like a note I’d often put in each year around election day or registration, just a civic reminder made in passing. But that night, multiple people told me it had bothered them for years (so I guess they heard it, anyhow).

All of which makes sense of what was to come, and another point of fracture for me. I got regularly attacked over the next few months over our COVID caution; it was public in the sense it was on social media, private in terms of emails and messages dropped by the church, and it wasn’t anywhere near a majority of church members. Maybe half a dozen.

But lots more than that, and I’d argue a working majority of active church folk, knew it was going on, saw it. Sometimes people would say something apologetic to me directly. I’d reply “would you be willing to respond directly?” In sum, the answer was always no, they didn’t want to engage. “Just let it roll off” I heard more than once. Perhaps I should have been more indifferent to it, but I will admit it was the sense that no one had my back that stung as much as anything that was said about me or my supposed gutlessness or spinelessness over not “facing facts” or “sharing lies.” We moved from online video worship to live video worship to outdoor worship, a drive-in set-up with a low-power radio broadcast plus the streaming video feed, each step calling for some interesting evolutions on skills and technology. It was both exhilarating, and exhausting, and meanwhile the complaints and criticisms continued to mount.

Increasingly, people would say “it’s really all overblown, isn’t it?” I should mention that my son lost his college graduation, and a planned overseas trip to Japan that May with the marching band he’d been in for four years, plus our plans to travel with them there. Yes, we all lost out on a great deal, plus high school graduations and weddings and many other events of that spring and early summer. We did my father’s memorial service at our home church outdoors, with more than a few logistical challenges, as churches were hesitantly starting to look at how they could return to in-person worship. The voices were getting louder, more insistent, and more directly challenging about both what should happen next, and demanding an admission that it shouldn’t have happened to start with.

Meanwhile, I’d done enough funerals (usually graveside only) & made enough hospital visits under extreme restrictions to know this was real, a problem, an illness which was resulting in fatalities. True, I could see then as we’re more clear about now, that this wasn’t shaping up to be a 1918 Spanish Flu global pandemic, with truly horrendous mortality rates, but it took months for us to know for sure, and to clarify who was truly at risk — nursing homes tragically turned out to be a major source of deaths — and I was and still am horrified by how many people were willing to dismiss most of the casualty figures with barely nuanced versions of “they were going to die soon anyhow.”

For the record? Ohio saw 1 in 300 die from COVID; states like Mississippi got to 1 in 200. I’m still not clear how many needed to have died for people to generally concede the precautions were necessary, but given that there were good faith reasons to believe it COULD have been more past the 1 in 100 level, at least at first, most of the recriminations strike me as 20/20 hindsight more than conventional wisdom ignored in a panic. Obviously, this is still a debatable point in many quarters.

Meanwhile, back at March 14, 2020, my sister and I got to Pharr South and hit another breaking point of sorts. Our mother was . . . off. And yes, she’d just lost her husband. We tried to allow for that over the next few days, but really, our early impression stayed valid: something was wrong with her. What casual friends in the retirement community could put down to a mix of shock and her own personal quirks, we saw pretty clearly was cognitive decline. She could not care for herself, and she certainly couldn’t live alone; not now, and not ever. Nothing over the next few weeks changed that early assessment. So we were looking at selling the modular home in Texas, which Dad had already been working towards, giving us a path forward at least, but also selling the home in Indiana which Dad had built much of, which all of us grew up in, and to which Mom occasionally said she wanted to go back to . . . but not with much emphasis. Going to my sister’s “for a while” was just fine with her.

My sister did all the heavy lifting, on paper and often in practice, to clear out the house in Valparaiso, and we ended up selling it after a series of plumbing misadventures and many, many trips to dumpsters all around a city mostly still shuttered for everyday activity. That was during the summer and into the first weeks of fall. On March 23rd we just bundled Mom onto a plane with my sister, and flew them back to Indiana; on the 24th, I loaded up a rental van and began a three day venture across five states to catch up with them, listening closely to the radio for odd developments like Arkansas closing its borders with Texas — which at one point was reported as coming in a day or two, but blessedly never happened.

To get through any possible obstacles along the way, I had Dad’s ashes on the passenger seat (along with stuff piled under them - that van was PACKED to the ceiling). How I claimed them on the 16th was a story that describes perhaps another crack in my brain, if not my heart, but it’s a long one and suffice it to say I was reminded of how the whole process of death and memorial and interment has changed now for all of us, and I don’t think for the better. Anyhow, it wasn’t what I’d ever imagined, but it was what it was, and I had them in my care as the rest of their everyday material gear in Texas hurtled north. As it happens, no one ever stopped me, but I was fairly certain that box and its label would get me to my destination.

I got there, we unloaded, I left my sister to her new responsibilities, and got in my car to head back to Ohio . . . to receive a phone call on my way east.

My wife was heading west, because her father had been taken to the hospital for a possible cardiac event or stroke. She ended up staying there a few months, but we never did find out what caused her father to pass out. He had a pacemaker, but no issues showed up from it, leaving the episode a mystery; ultimately I would end up moving in myself with Buck for over three years until his death last December, because he was increasingly disoriented and unable to care for himself. My sister and mother came to his funeral on Dec. 23, 2023; a year and a couple of weeks later we would put Mom in memory care because of how much worse her cognitive issues had become. In between I tried to recover some semblance of full-time employment for myself, but it appears my resignation in August of 2020 was the end of that. Call it a break.

Meanwhile, I have a marker placed on my parents’s grave in Valparaiso, but am still working on getting that process completed in Indianapolis where in fact both my mother-in-law (who died in 2015) & father-in-law are interred. In the process of getting that marker completed for both of them, they told me the granite stone is cracked and will have to be replaced, too. Poetic, ironic.

Just to be clear, my life is rich and full and good. Many things I’ve worked for, and much about my family, is in a very good place for which I am truly thankful, or at least trying to be as thankful as I ought to be.

Where I’ve found the most healing over the last few years is in teaching Disciples of Christ history & polity, mostly through the Phillips Theological Seminary “Center for Ministry & Lay Training.” Since early 2022 I’ve had over 200 students in this course who are in some cases commissioned ministers fulfilling their requirements for standing, but quite a few who are ordained in other traditions, coming into the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and seeking recognition & standing, often as they already are serving a Disciples congregation. So I get a mix of students literally from the Atlantic to the Pacific (my current course cycle I have students serving within view of each ocean), a variety of regional Commission on Ministry expectations, and anywhere from having a high school diploma only to their being doctors, deans, and judges outside of their ministry service.

In and out of those three course cycles a year (the class is eight weeks long in what’s called an “asynchronous” platform for online learning) I’ve also gotten better at doing congregational leadership or Sunday school class teaching on Disciples history & polity, through live conferencing or making video presentations they watch on a Sunday morning while I’m supply preaching somewhere. This has given me the opportunity to share our story with hundreds more, again all over the continent, not just in Ohio.

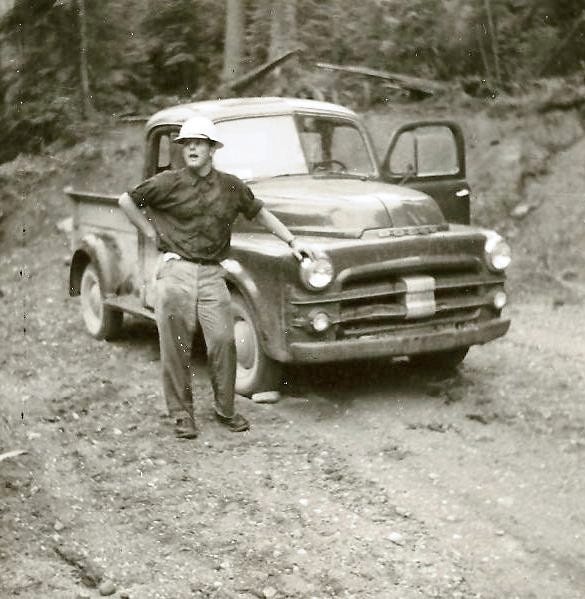

One of the last extended experiences I had with my father was in his home state of Des Moines, at the 2019 General Assembly, right before the world changed so much for all of us. He sat in on my two-day history & polity training for (mostly) commissioned ministers, across a six hour total instructional period. Afterwards, I asked him what he thought, the man who gave me his interest in history and how the past lives in the present. “Not bad,” he said.

I knew that was all I was going to get out of him. I know he was proud of me, because I heard about it . . . from lots of other people. To me, that wasn’t something he was going to say. Over the years as I learned about his father, and grandfather he never met (just as I never met mine), I understood more about where that reticence came from. Living with my father-in-law as long as I did before his passing, I got a better sense of where his defenses were high, and perhaps why.

Dad’s passing leaves a hole, and that’s to be expected. In the same way, having turned a page, even a chapter or whole section of my own life leaves what feels like a gap, a missing transition. Sometimes in a big book there’s just a blank page between sections of a longer story to tell.

Laurence Sterne in “Tristram Shandy” included, on the death of a significant character, a black page; some critics suggest he was both mocking and avoiding the sentimental tropes of his day in describing a death-bed scene.

Maybe that’s just it. A black page, then onwards. (Rothko would approve.) I’m just not going to be able to make sense of this turn of events. We are five years after my father’s death, and the relatively unrelated advent of COVID as a pandemic on the same day, with at least 1,200,000 deaths in the interval since credited to the novel coronavirus. We’re still arguing over where it came from, how it was first spread, and what we should have done to mitigate it, up to and including vaccines today. The dialogue seems if anything less productive than it was when my sister and I were watching White House press briefings in March 2020, while trying to figure out how much of fifteen years of debris could be wedged into two suitcases and a rented van (plus a black plastic box containing a bag full of ashes).

But Dad’s death, parish ministry, and public health all still feel tangled up and connected and unresolved to me, in some inextricable but unavoidable way. These days I’m doing some ongoing supply preaching at a tiny church, twelve to twenty people a Sunday (thirty on Christmas Eve was cause for celebration), almost all most weeks over 70 years old. There was something following a program recently where something needed cleaning, and I was looking for means with which to clean it, and a church leader laughed at my question, waved a dismissive hand, and said “if it’s going to kill someone they were probably going to die anyway.” She will never know the rage that boiled up inside me as she walked on out the door. I cleaned it up anyhow.

It’s that spirit of “Devil take the hindmost,” or more specifically “the strong will survive but they shouldn’t be handicapped to protect the weak,” or even “if I don’t like it or understand it then it must be evil and wrong,” that seems to have surged back to the fore not just in our civic life, but within churches. At times I want to preach I Corinthians 8 at length, for weeks on end, until there’s some measure of understanding. Christian community and public health are not in opposition to each other, even if we might leave room for a diversity of opinions about vaccines or masks or epidemiology. And others have said more and with more wisdom than I possess on how politics and congregational life have gotten toxically entwined, with matters of public health simply one strand of a tangle worse than anything Clark Griswold ever took on.

This is, in other words, a fifth anniversary for much more than one man’s loss of a father, but for me it will always be combined with that. I’ve been asked a couple of times if I will be writing in my newspaper column(s) about where we are now, five years after COVID. As with my rage the other day, I’m not sure I have the self-control it needs to speak helpfully on the subject. Too much emotion, still too close to the surface, and perhaps not adequately integrated into a coherent whole . . . more likely to come out as a towering tirade than a reasoned presentation. More hot-tempered rants are not what any of us are needing these days, or so I perceive.

Meanwhile, the needs of community, of my own community, continue. And I feel called to help serve my community because of, well, my dad. That’s how he raised me. Even if the community sometimes seems hell-bent on putting up divisions, excluding the weak, protecting the strong, focusing on winning with indifference to the costs of losing. You keep on, because caring for the young and the old, looking out for those who can’t look out for themselves, is a holy calling. That’s what Dad taught me.

There’s work to do. We’re burning daylight. Onward.

A gift link on the underlying symptoms: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/03/experts-failure-covid-19-pandemic/677816/?gift=otEsSHbRYKNfFYMngVFweKyEcFZkd-afqNk-J56enMA&utm_source=copy-link&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=share

"And yet, the U.S. still lags the rest of the developed world in protection against COVID-19. According to the CDC’s most up-to-date data, from 2023, some 70 percent of Americans received an initial vaccination, but fewer than 20 percent have had any booster. The rates are much better among people over 65, who—for various reasons, including their awareness of the disease’s increased danger for their age group—are more attentive to getting vaccinated.

The ultimate numbers, however, obscure the deep political divisions over vaccination, preventive measures, and science itself. A New York Times/Siena poll in 2023 found that nearly 70 percent of likely Republican voters would trust “the common sense of ordinary people” over “the knowledge of trained experts.” (In a Pew poll a year earlier, 51 percent of Americans said that public-health officials had done an excellent or good job at managing the pandemic, but that number was anchored by the 72 percent of Democrats who felt that way; only 29 percent of Republicans agreed.)"

Hat tip, @timtrussellsmith911599 for connecting me to this post on today's "anniversary" of sorts: https://laurastephensreed.substack.com/p/its-been-five-years-since-lockdown