We like our stories to be tidy.

I know, some of you like horror or old film noir, and wouldn’t be caught dead watching a Hallmark movie. You’re in a minority. Are you “right”? Nah, it’s a matter of taste. There are people who’ve never watched a Star Wars movie, or a Marvel Cinematic Universe movie. But Hallmark Channel films capture a remarkable swath of the population.

One thing I believe history does for us, if you engage scrupulously in it, responsibly using secondary sources to get to primary sources, and assess them honestly — history rightly considered will always tell us that life is not tidy. There are patterns or themes that recur, and we can and must use some time saving devices to sum up just like rom-coms use montage sequences to jump ahead in the story, but history as it really was is messy. Untidy. And that’s the most reliable thing history can tell us about the future. It’s gonna be a mess. Any guidance beyond that in predicting the future from past events is asking a great deal of historic parallels, or as the investment folks like to say: “past performance is not indicative of future results.” Because they know their history.

History is rapidly losing popularity. It is perhaps fair to say we generated in the last few decades way too many history majors and PhDs for what the market would bear, but I’m talking about the overall social attitude towards history, especially in church life. I get a compliment sometimes which I feel uneasy about, as a teacher of Disciples of Christ history and polity, and also as a site interpreter for our UNESCO World Heritage List earthworks in my community: “If I’d had you as a teacher for history, I would have been more interested in it!” It may be true I do a good job of helping people make connections to the past, and drawing the story together in a coherent narrative, but if it’s just about charm and charisma that’s too bad. We’ll leave pedagogical theory and non-formal education for another day.

Specifically, I notice — because it is my job, so to speak — how in the early days of the internet, almost every congregation had a tab or link on the splash page marked “History.” I gobble that stuff up like Chex Mix. But then I noticed after a decade or so, the “History” click went deeper into the site, one option under “About Us” below “What to expect when you visit” and “Staff,” or even further down.

Then it vanished. Frankly, a “History” tab is an anomaly these days, and often it’s there because a church hasn’t updated their website in seven or eight years. Increasingly local church websites prefer to bury their denominational affiliation, which can be an interesting puzzle to sort out (quite a few Southern Baptist or Assemblies of God church plants have that connection three or four levels down on their website), and of course a new church isn’t going to have much history to put under a “History” tab . . . but until recently even a young congregation would have at least a page with a few paragraphs about their start and journey to their current location.

Now even long-standing established congregations just skip the “History” issue altogether. People aren’t interested.

I remember Clark Williamson, peace be upon him, chortling in Cincinnati in 1999 over the nod to our 150th anniversary meeting there (our first “general” ministry being the 1849 American Christian Missionary Society, whose secretary elected at that initial gathering in the Queen City was Alexander Campbell). There was a mix of slides and tableaux, which started with Jesus and the OG Disciples in 33 AD, and basically a leap to 1517 and Luther, then it’s 1804 and we’re at Cane Ridge. “That’s how we look at history, one giant leap after another,” Clark said, I’m sure saluting Ohio’s own Neil Armstrong. His point being we have a strong American tendency to ahistoricism.

Which skips over a great deal of messiness, which if we could see it more clearly, might help us face our own messiness, let along make us realize there’s no way in actual life, church life or otherwise, to skip over the messy parts. Or to resolve them neatly one hour and fifty-eight minutes into the two hour run time with a kiss and a happy ending.

We completed last month our General Assembly in Memphis; I wrote five posts about the event as it happened from my admittedly narrow point of view, with some tentative conclusions in the fifth. Inside it at the bottom are links to the previous four:

General Assembly 2025, tentative conclusions

This is my fifth & final entry about the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) General Assembly in mid-July of 2025; links to the previous four posts can be found at the end of this one. Keep in mind I arrived in mid-GA, missing the first two days of the four. I had hoped to make it in time for the evening worship on Sunday, July 13th, but heavy rain &…

What I think I can say as a somewhat still working minister in my tradition (36 years ordained yesterday, thank you, with eight years of student ministry before that, and currently stated supply for a Presbyterian Church USA congregation) is where I tried to land things in the post above. We have seen in my years aware of regional & general church life, versus the purely congregational perspective of a child, a shift from the late 1970s into the 2020s away from an Institutionalist view of church life for Disciples of Christ leaders, laity or clergy, to a more Idealist perspective.

This tension between Institutionalism and Idealism is less between factions of individuals who are purely one or the other, than it is a shift internally of priorities. In the 1950s we had some strongly Institutionalist leaders who were very Idealistic in certain ways; today we have many Idealist leaders who have enough Institutionalistic sympathies to keep our board and councils and commissions functioning well. I have identified in my earlier writing, and work as a regional leader, some issues that arise when Idealists look at matters like invested funds and trust accounts, and their Institutional commitments for the longer term good of the organization or facility take a back seat, leading to what I’ll just discreetly call “excessive draws” on those capital sums, reducing them in some cases to near zero (or worse).

Keith Watkins, the father of former General Minister and President (GMP) Sharon Watkins, wrote a history of the seminary where I took classes from him, Christian Theological Seminary (CTS) in Indianapolis. This 2001 book among other things outlines how over the last fifty years CTS managed to draw down their funds to nearly zero not once, but twice; I’m not privy to Board of Trustees discussions more recently, but I think it’s safe to say it happened a third time. They dodged the bullet where Cincinnati Bible Seminary did not (it closed in 2019 just before COVID would have iced them in any case), but I think you can see in their story an over-balance of Idealism vs. Institutionalism.

If you’ve not read my writings about “The Rise and Fall of the Ohio Region” let’s just say it’s 90,000 words on the same problem.

Some will say — some have already said to me, personally — that a church, certainly a Christian church, should never prioritize the institution of the church over the ideals, the beliefs we hold to be good and true and beautiful. I agree wholeheartedly. My point is that if you get too idealistic, and become too dismissive of institutional norms, you can end up losing both your institution and your ideals. Hence my call for a balance between Institutionalism and Idealism in our search for leaders and priorities and mission for the church of Christ, whether local, regional, or general.

And my last entry raised a concern about the rise of a third factor in our church life, as to Activism, which is a particular sort of institutionalized idealism. I used three examples to make my point: Samaritan’s Purse, Lifewise Academy, and Repairers of the Breach. You may like one or two and have distate for the other in any combination. My worry is that Activists for outside organizations are prioritized on their cause, their agenda, and their organization; they don’t wish us ill, but they aren’t worried about our long-term health or short-term viability. To be a bit cruder about it, they want your best givers for their mailing lists, because that’s what keeps them running. They need those “sustaining gifts” of “just $19 a month” and if you think your Idealistic church member won’t end up giving less to your congregation’s stewardship campaign after signing up for five or six “just $19 a month” obligations, I have a math problem for you.

I’m not knocking that stuff. There’s all sorts of it out there. I’ve shilled for it myself.

Yes, that’s me holding my infant son in 1998 about to eat a dog biscuit because of an on-air challenge to get at least five more $100 pledges before the segment ended . . . and my co-host had lawyer friends watching who got us a cool $1000. They’re very dry, by the way.

More recently:

So yeah, fundraising and audits and bylaws and procedure and media relations is all very Institutionalist. But to get my Idealistic goals met, I gotta know how to work those angles and impulses. I think there’s a balance to be struck. But it’s hard, especially because . . . life is messy. And history is not tidy.

We Disciples of Christ regret the splits we have in our history, but we also tend to gloss over them, like the 1999 giant leaps from Jerusalem to Wittenberg or from Germany to frontier Kentucky. There’s a perfectly natural tendency to see them as growth, followed by disputes over principle, Ideals even, in which we were right and those who were defiantly wrong left, which surely helped as we moved forward with a more cohesive, unified church.

Ahem.

I should say at the outset this isn’t entirely wrong. There was a split between the folks who didn’t want missionary societies or musical instruments that started in 1867, the year after Campbell’s death, and was formalized in 1906 by David Lipscomb; that led to the a capella or non-instrumental Churches of Christ as opposed to, well, us as the Disciples of Christ. See https://www.midway.edu/about/melodeon.html for a sidelight on this.

Then we got into a battle which started with whether or not our missionaries in Mexico or the Philippines or China could or should work in cooperation with other Christian groups like Baptists or Presbyterians or Methodist, picked up some tensions around John D. Rockefeller’s money versus the benevolence of a oil patch competitor of his who chose not to be bought out by him named Thomas W. Phillips (yes, that Phillips), which spilled over into a mix of higher criticism of the Bible and acceptance of evolution as a viable theory in science and life starting at our College of the Bible in Kentucky (now LTS) and rippling out from there in the pages of the “Christian Standard.” This split starts in 1901, intensifies in 1920 with the formation of the United Christian Missionary Society (UCMS), opens up visibly in the 1926 Memphis walkout, and is somewhat finalized by the Disciples of Christ adopting Restructure in 1968.

The Hallmarkian version of all this is “bad views and stubborn people left, in two cohorts which became definable groups each in their own right, while we stood together as an open and accepting ecumenical Christian movement.” Like the end of a Hallmark movie, I almost hate to interrogate that outcome. It’s like asking as the credits roll (and the next movie starts) “but won’t they find it hard to get enough business in that location to pay for the staff and allow them to start a family?” No one wants to hear that noise. They kissed, just smile and applaud.

And the a capella Churches of Christ, and the independent Christian Churches, are both having their own troubles, in identity and viability, both on the local and wider levels. I keep up with enough of their members and ministers to know their clergy compensation makes ours look stellar, expectations for pastors are as excessive as our own tend to be (YMMV), and they’re closing up church after church in rural & even suburban locations at a rate that doesn’t look too terribly different from our own. Their intense independence, which is part of what led them out of our branch of the movement, means record keeping and hard data is even harder to find than for most.

So it’s not as if I’m working my way up to saying they have something we could learn from. I think their approaches were off-track, and the splits were essentially unavoidable at least by the time they occurred (hold that thought). But we do share a great deal of history, and some of the flaws might be instructive to us as our form of Christian faith and practice is under increasing stress, post-COVID and during the Trump era. (If you don’t agree that the Trump era’s polarization is putting stress on congregational & church life across the board, you can probably stop reading now.) Their flaws are, in no small part, our flaws.

For instance: in my research around the rolling centennials we’re observing across the Midwest around the Ku Klux Klan, there’s some shared flaws we need to acknowledge. Madge Oberholtzer died 100 years ago this past April, of the assault committed on her person by Grand Dragon D. C. Stephenson in March of 1925; his trial for her rape and murder would take place in October & November of 1925, and his conviction & failed appeal would lead to a general collapse of the Midwest Klan in 1926. The 1920s era Klan before that implosion was hugely influential in my hometown of Valparaiso, Indiana and also, as fate would have it, in Licking County, Ohio. The Klan candidates in Newark, Ohio would take the mayor’s office, a majority of the city council, through them the chief of police, and a number of other county level offices including at least one judge from 1923 into 1926; Stephenson himself owned a home on Buckeye Lake and visited here on multiple occasions.

When we look at the vexed period between 1919 and 1926 for the Disciples of Christ, and the growing dissension leading to effective splits in places like Ohio over questions about the formation of the UCMS, and the growth of parallel institutions for the independents like Cincinnati Bible College and Round Lake Christian Camp, it’s hard to avoid noticing that the period of maximum tension overlaps precisely with the rise and pinnacle of the Klan’s authority in Ohio and Indiana and Kentucky in particular.

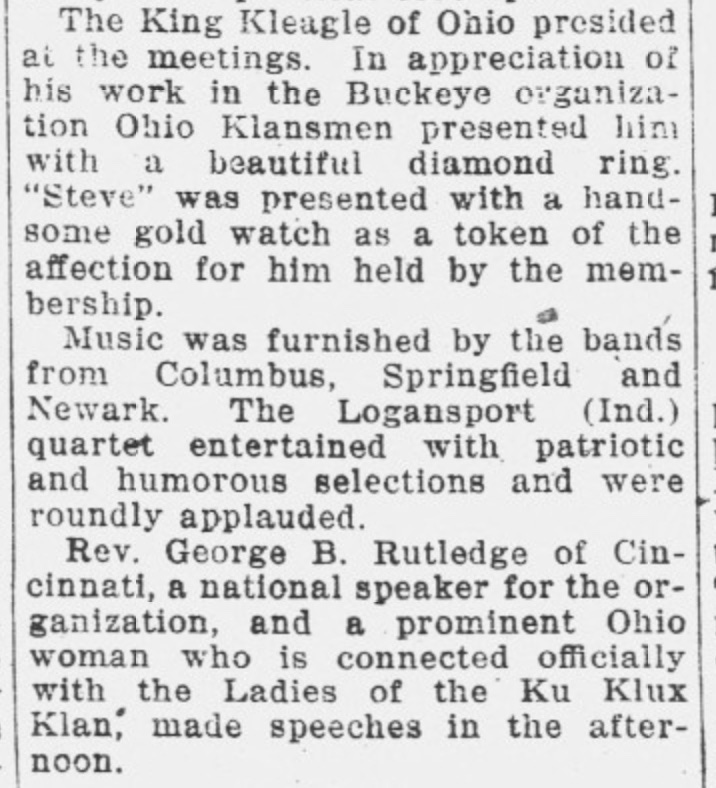

And as I looked at what information I could glean locally about Klan activities in 1922 through 1926, I noticed something. This is from a Klan paper about their 1923 rally at Buckeye Lake which was said to have had some 75,000 in attendance.

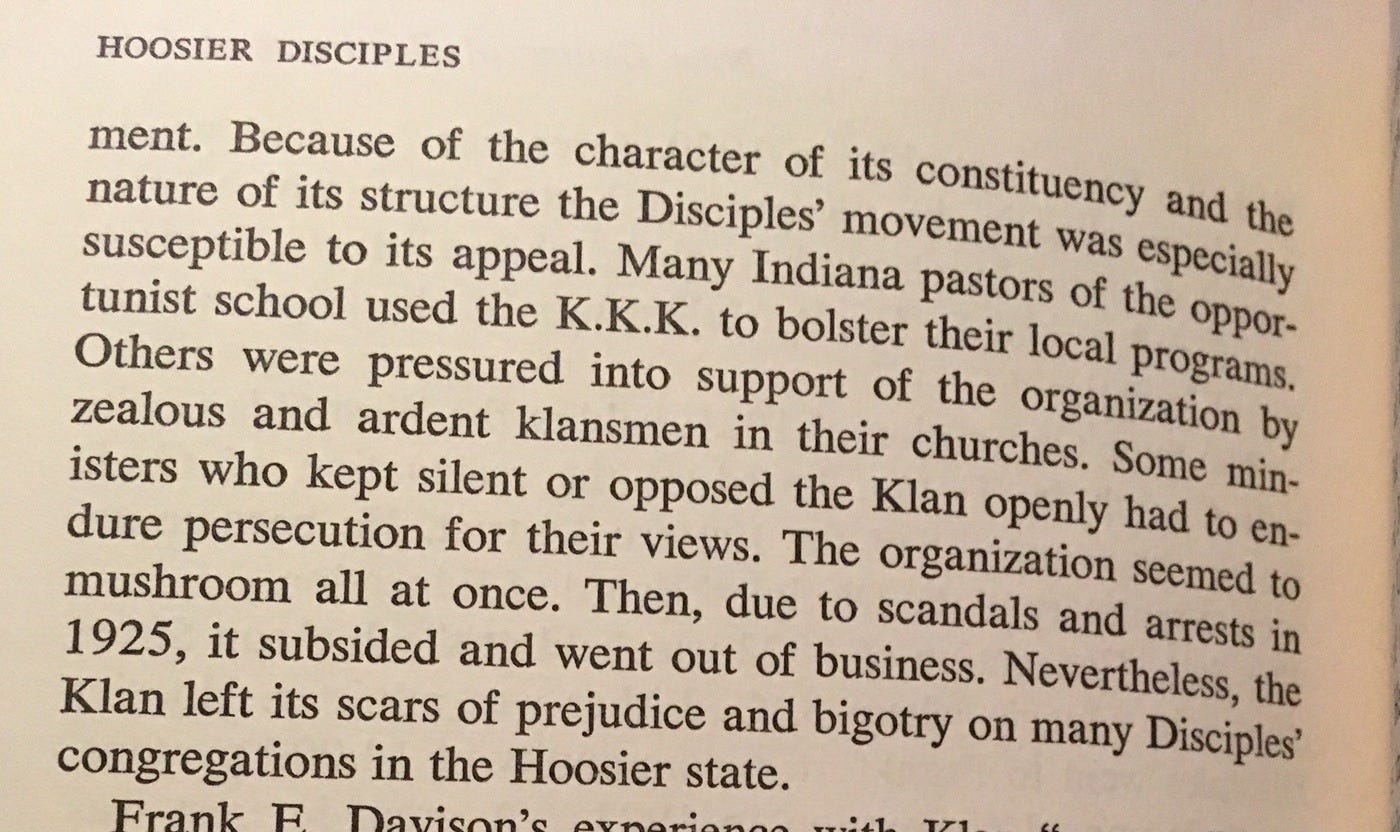

George Rutledge was, from 1917 to 1922, the managing editor for the "Christian Standard." Before that, he was pastor of Broad Street Christian Church in Columbus, Ohio. After 1926, he goes back to being a Disciples of Christ pastor.

Which is interesting, and a bit odd, because finding this specific mention made me hunt around (research is too grand a term for my sporadic but persistent online efforts), and I came up with a factoid that should not have surprised me, but did. During this period, “Christian Standard” had to the best of my knowledge eight men who served in editorial roles, including “office editor” or managing editor, as Rutledge was from 1917 to 1922, all under an overall manager (or CEO) of Standard Publishing Company. Of those eight editors, I can find clear, specific confirmation that four of them served as state or national lecturers for the Ku Klux Klan. Some like Rutledge moved on up into a full-time role as a national official, while state lecturer seems to have been part-time and those persons stayed at work with the “Standard.”

Four of eight. Half. Except I can’t say for certain none of the others were, just that I have no specific mention of their having been so employed. As you can see from the above excerpt, some Klan speakers were fine with having their name out there (which says something, doesn’t it?) and others not so much (“a prominent Ohio woman who is connected officially with the Ladies of the Ku Klux Klan”), with the latter much more common. “A fine young man of the city” or “Our much respected leader” is usual.

I got into this, in fact, trying to get to the bottom of my adopted home’s story, and a pulpit which I recently served. A predecessor almost certainly was the county Klan chaplain, or Kludd; I have him accused of being a Klansman in print, on the pages of a newspaper from out of state, and he would leave — in 1926, in fact — for a town which stayed Klan supportive into the 1930s, but intriguingly a 1950s congregational history here notes the records are . . . missing, for exactly that period of his ministry.

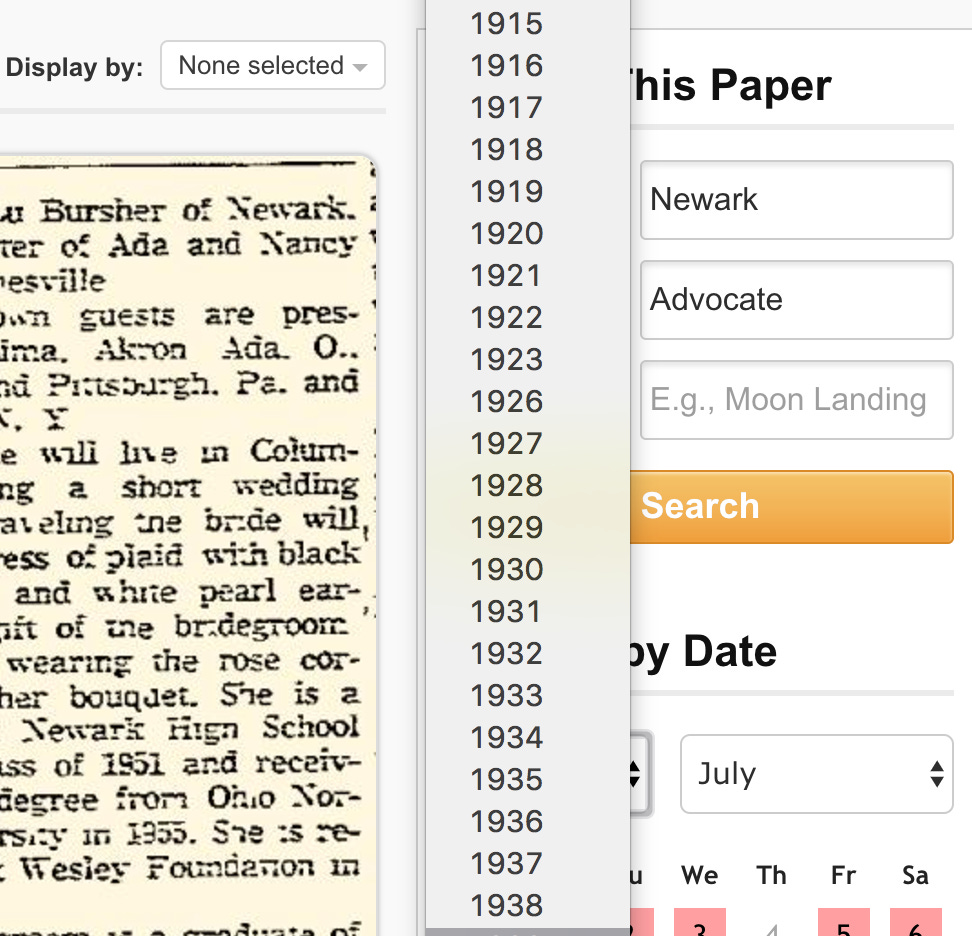

Our local newspaper, if you look online or in any physical archive in Ohio for it, shows what you can see below: no copies at all for 1924 or 1925, and when you go into it the last half of 1923 and the first half of 1926 are missing, too. The entire period of Klan control of the city and county has been vanished, I suspect by people who felt it was best to just disappear the whole sorry story.

In Ohio more generally, a history written twenty-five years later, while many eye-witnesses would have been around, has just this to say about the Klan era and Disciples of Christ:

Henry Shaw would write a few years later a similar passage for Indiana Disciples:

That’s the story. And how it has been passed down: it was a craze, it only caught on in a few places, and it passed quickly. Uh huh.

My “Christian Standard” discovery, starting with Rev. Rutledge, should support this narrative. Four of eight masthead editors working with the Klan? And the “Standard” the primary mouthpiece for separatism, traditionalism, and ultimately independent institutions from the UCMS rooted Disciples of Christ? Yay us, boo them, right?

Alas. For one thing, the story of the “Standard” is a little more complicated than that. It was hostile to Rockefeller money and unified promotions and cooperative missions, true, but it really didn’t become a vital and even virulent force for caustic language about the “cooperatives” (i.e., us Disciples) and emphatic calls for division until the 1940s. They weren’t fighting for a complete separation in the 1920s, or for most of the two decades afterwards.

The other problem is the standard (sic) narrative about our brush with the 1920s Klan implies that, as my survey of “Standard” editors suggests, it was churches which would end up splitting that were Klan supporting, while the congregations which would maintain ties to the Disciples and the UCMS and the International Convention, later our General Assembly, were valiant Klan opponents. But the evidence, somewhat to my surprise, is the exact opposite.

It is a mix, and depending on how you do the math, you could convince me it’s more like 50/50%, but if you scan the pages of the official Midwest Klan newspaper, a weekly from late 1922 to early 1925, you’ll quickly see what I did: most of the Christian Church congregations that hosted Klan events stayed Disciples of Christ. Some have since closed in the last thirty years, some went independent post-1990, but in general, most of the churches with open, stated Klan associations stayed Disciples after 1926, especially if you add in information from other newspapers when you can find them.

History is messy. The lines that divided us aren’t as easy to trace as our tidy storytelling likes to claim. I DO think there’s a huge amount of racism involved in what motivated the “Christian Standard” and the Memphis walk-out separatists. The whole urban-rural thing about the post-war a capella Churches of Christ vs. the Disciples of Christ, and the echo of those class issues into the rhetoric of Professor McGarvey and his supporters down into the independent North American Christian Convention wing which would slowly but steadily peel away from the Disciples of Christ who stayed with cooperative missions, it’s there. It’s real. We never really did well in cities, but as our movement spread into county seat towns, and on the edges of cities, there was a tension between those more aspirationally oriented congregations, socially speaking, and the smaller rural churches which couldn’t afford a pipe organ or to send money to Indianapolis, and they made a virtue of it.

But that aspirational element of former farmers who had moved into county seats and small cities, and were working up a social ladder which they knew they were on the bottom half of, still: that’s exactly the audience the Klan was aiming at. Seriously, swallow hard and scan some of the content. You’ll get surprises. Especially if you grew up in the Midwest.

https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=cl&cl=CL1&sp=FC

Am I trying to say today’s Disciples of Christ still have a whole bunch of Klan heritage in their closets? Well… not exactly? But yeah, I am. And it’s hard to talk about. It’s easier to say “those people left” or, more recently, it’s about “let’s make sure those people leave.” Except they didn’t leave: I have had not one but THREE separate pastoral conversations, in three churches, with people who came to me with Klan robes in the closet. Literally. They were the possession of fathers and grandfathers. We talked and prayed and cried and I helped make contacts with state historical societies. They loved their family members, and they were & are horrified by this aspect of their past.

My wife & I have talked about this in our own families. Looking widely at our ancestors, we both have Klan involvement in our bloodline. It’s not someone else. Our parents said good and true things to us about people and humanity and justice, but not far behind them, genealogically, are robes and flaming crosses and an implacable hatred for people different than them, at least for a few whose names we know, whose graves we’ve tended. I’ve written elsewhere about a neighbor on my paper route in the early 1970s bemoaning that I didn’t have a Klan to join, and how he treasured his riding with both father and grandfather to nighttime cross burnings. My father helped write our congregational history in that town, where it is true the church voted to not allow the Klan to meet on the premises in 1924, but he was pressured to delete passages from a letter sent them by a now elderly daughter of that minister, who recalled how they left town after the third cross was burnt on the parsonage lawn. We kept in our history the story of turning back the Klan, but edited out how we couldn’t protect the minister afterwards.

Or I could just say this: two things can be true at once. The “Christian Standard” through the early 1920s was steeped, saturated in Klan propaganda, even if they kept any mention of the Klan out of its pages — which is fascinating in its own right. After Rutledge resigned as editor to work for the Klan, his old employer in 1923 was happy to take out ads in the primary Klan paper:

But it is also true that Disciples of Christ churches across the Midwest, ones that stayed with the more “mainline” and ecumenical body, were as likely if not more likely to get sucked into Klan involvement . . . which was more engaged in conspiracy theories and hate speech about Catholicism in this part of the country, while they were still plenty hateful towards Blacks and Jews. Our churches, our elders, and yes, our ministers dove into those murky waters, and after they clambered out of the swamp following the disgrace and conviction of D. C. Stephenson, the whole experience was largely brushed aside, even if the stench of foul waters was still in the air.

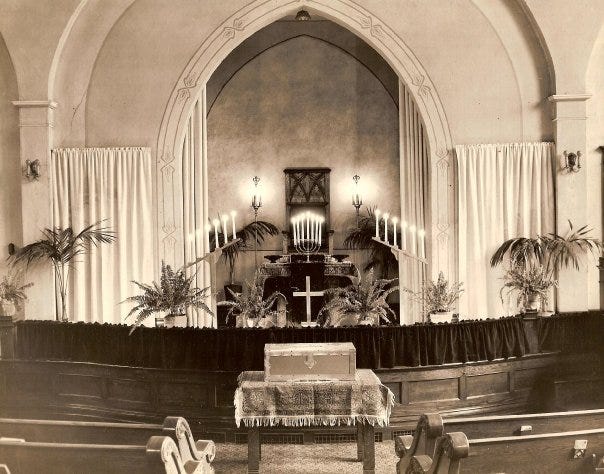

In fact, the hardshell independents were remarkably resistant to Klan appeals, most dramatically in their usual approach of bringing a United States flag in high quality silk with gilded stand and finial on a sturdy pole, as a presentation to the congregation which they chose to favor with a “church visitation” by a procession of silent, hooded Klansmen, along with an offering in cash or coin. They would arrive silently, deposit their gifts, and depart just as quietly — the noise was inside the church afterwards, when the elders and preacher had to decide what to do with the money, and with the flag. Most just put it up.

Old school Restoration Movement churches? They wouldn’t do it. In fact, if you go into most a capella or independent Churches of Christ, you won’t see a flag in the sanctuary, to this very day. Disciples churches? We almost all have them. Check the archival photographs: you won’t see them before about 1920 or so. Hmmm.

It would tidy if we could put the whole weight of Klan-era racism on the independent branch of our movement, which did split off over many social, theological, and politically conservative concerns. I think a number of their leaders, including George Rutledge and Willard Mohorter at the “Standard,” were happy to use racism as a wedge issue. But racism alone isn’t the sole, tidy, comprehensive reason for the split if “our side” carried an equal burden of that failure through the period. I’d like to think it’s a bit of the guilty conscience we held onto which helped us get serious about being anti-racist and pro-reconciliation after the 1960s, but as a historian and as a theological educator, I’m skeptical, and I’m concerned at the lack of reconciliation work we’ve engaged in, about these painful events which are directly located in our history.

Undone work tends to pile up and back up and add to the mess. This is why I think some historical awareness, in congregations and for ministers and across our wider church expressions is so important. We’re entering another period of radical change in our overall make-up as a church body where I worry we could be repeating old mistakes, and stumbling over unresolved issues as we try to deal with current ones.

My historical sense is, reading the primary documents and critical secondary responses from the earlier divisions in our church life, again and again we have thought “if we can just get rid of the people and church structures and congregations which are holding us back, we will be all the better for it: more faithful, more efficient, and perhaps smaller for a while but better positioned to grow with like minded people.” One version or another of this hope shows up over and over again.

I hear this in the Campbell Institute discussions and reading back issues of their publication “The Scroll” on the progressive side in the 1920s & 1930s, just as I do in the “Christian Standard” and “The Lookout” as it gets more and more shrill about modernism and accommodationism and the evil of “open membership” (not requiring un-immersed believers to be rebaptized). Agree with us, or leave. Don’t let the door hit ya’ . . .

The evangelist and editor Benjamin Franklin certainly strikes this tone in early battles over missionary societies and musical instruments, as does his heir Daniel Sommer, versus David Burnet and Isaac Errett in the pages of the earlier, more inclusive, pro-cooperation “Christian Standard” where rhetorically the same drama played out: agree, or get out and go where you’re more comfortable. James McGarvey in the pages of the “Standard” got more polemical about his particular Biblical interpretations as the century turned, to which J.H. Garrison pushed back, if gently but sometimes pointedly, in “The Christian-Evangelist.” It’s a recurring theme all through our history, back to the “conscientious sister” from Lunenburg, Virginia who challenged Alexander Campbell about rebaptism in 1837, and echoes down into our current era, the Trump era, you could call it. Polarize the options, intensify the tensions between them, increase the height of the barricades, tighten up the definitions of who is in, and the majority who should be out.

We’re one split away from getting being Christian right!

Except, as Rocky said to Bullwinkle, “that trick never works.” It never has. We keep peeling off dissent, but somehow it’s still there. Or it bubbles up yet again.

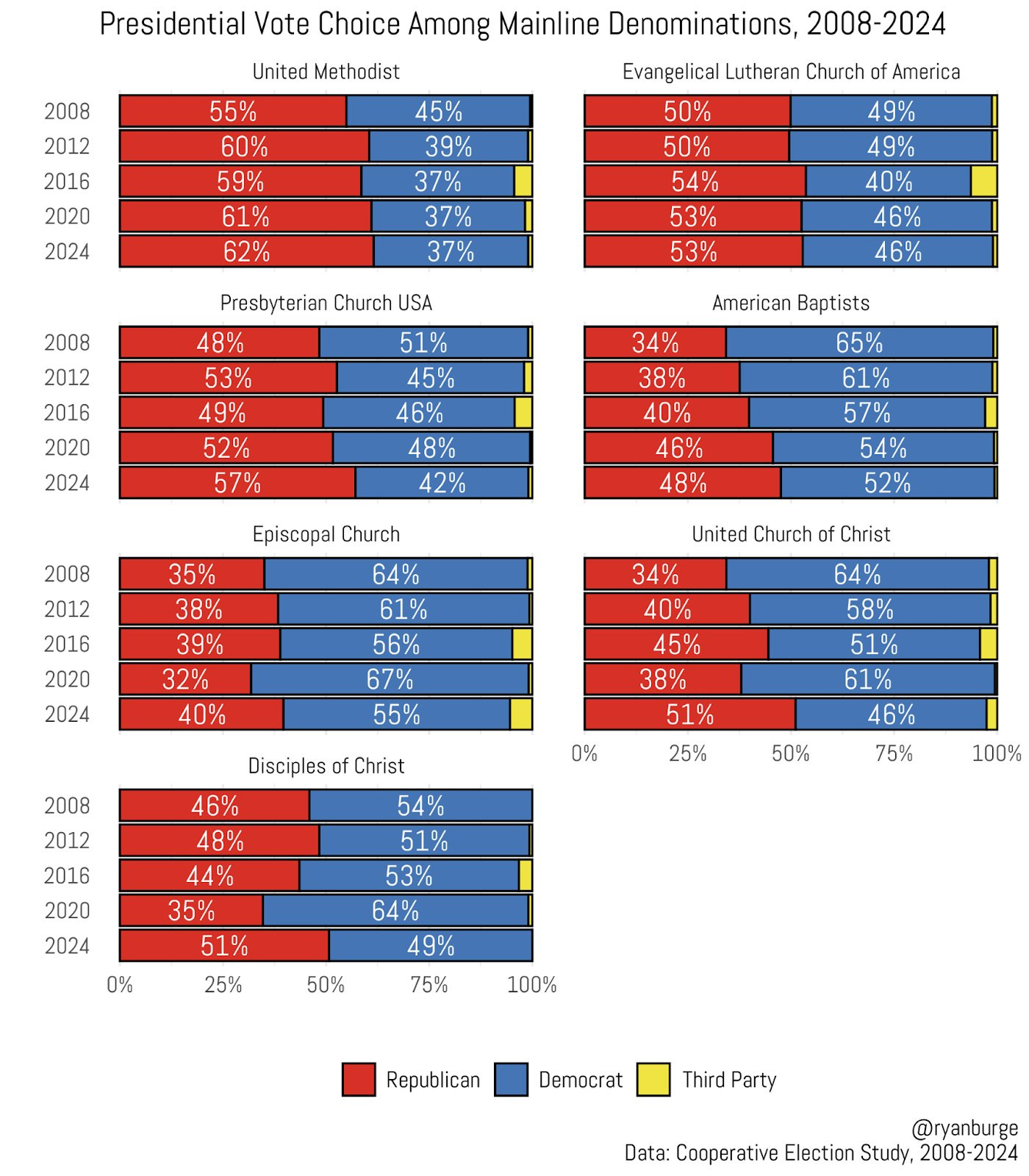

You could say “maybe we’ve gotten there, look at what you said about opposition at General Assemblies in your last post?” It’s true that voices against motions have become much quieter, if not silent, on the plenary session floor. But I’ll post that Ryan Burge graphic again about mainline Protestant church groups and presidential voting since 2008:

Call me crazy, but I think we need to figure out how to communicate with that 51%. Who, I suspect, have just stopped going to General Assemblies (go back a few more posts), but are still in our congregations, serving at our tables, and supporting our budgets. They’re apparently about half of our membership, even if you prefer not to use that term.

As a matter of fact, I think it’s time some 5,000 words in, and safely past the point where casual readers will have bailed out, I need to make a confession here. My name is Jeffrey Blaine Gill. Blaine was my father’s middle name; he was the sixth child, and all the family names had been used, so Grandma Gill recalled a name her father admired. Sen. James G. Blaine, the Plumed Knight from Maine. Yes, the Republican who campaigned against “Rum, Romanism, and Rebellion” and got his hat handed to him. He ran against Grover Cleveland, and his minions were allowed to foment anti-Catholicism as an appeal to working class Midwesterners, and it cost him in New York and elsewhere.

In Pennsylvania, he did okay. My maternal grandfather worked hard for him in 1884 as a Republican Party county worker in Pennsylvania, which Blaine won. Family tradition says Albert Kern’s father was a Lincoln supporter; Albert’s daughter, my grandmother, surprised me near the end of her life when I wheeled her through the Herbert Hoover Birthplace Museum, and she wept, speaking of her love for Mr. Hoover (and a few caustic comments about FDR). She named her youngest in part for . . . a failed GOP candidate, albeit one who was once Speaker of the House, a U.S. Senator, and Secretary of State.

Or to put it a bit differently, while I’m sixth generation Disciples on my mother’s side, I’m fifth generation Republican on my dad’s. Yes, I’m a Republican. Registered as such in 1979, consistent voter on both primary and general election days, known in my community as one of the first couple voters at the door when they unlock at 6:30 am.

Republican? I was on my county central committee for a number of years. I consider myself a capital-C Conservative, politically speaking. No, I didn’t vote for Trump, not in 2016, not in 2020, not in 2024. My father did, after voting twice for Obama — yes, they exist, Obama voters who pivoted for Trump in 2016 — and if he had lived, he’d have voted for Trump in 2020. We had words about that.

I argued, loudly and at length, with an old friend and Republican county commissioner, in 2015 in a public place about the general imprudence and foolishness of supporting Donald Trump as a primary candidate. He said Trump was the future, I said even if he accomplishes what you hope, his character and approach will damage the party for generations. This was BEFORE the “Access Hollywood” tape came out. I’m sure he thinks he’s taught me a lesson, ten years later.

However, I’m unrepentant — yet that’s not quite the point. Whether “Never Trump,” or a MAGA fan, we’re out there. Remember, the Ryan Burge data shows among Disciples we had 51% who voted for the guy, which I did not. So the net number of both Trump supporters plus Conservatives who can’t stand the man, is a figure somewhere upwards of 51%. I don’t like being lumped with MAGA, but for now I’ll accept it to make my larger point. Are we really intent as the Disciples of Christ to usher out the door everyone who is somewhere to the right of Kamala Harris?

Because frankly it sounds that way sometimes. Especially online, which is a risky sample to use for anything, I’ll admit. But in my interactions with Disciples clergy generally, and in reading our regional and general output, I trust I can be forgiven if not for being a recalcitrant nonconformist Republican, at least for thinking the tone of our discourse is around “get these people out of here.”

I am opposed to Christian Nationalism, appalled by Doug Wilson’s “theology” (if it’s worthy of that term), and worried about our civic & legal support for the rights of LGBTQIA+ people. If you think “how can you be any sort of conservative and say that?” I’ll just reply I have that conversation not infrequently. My biggest public profile in this community is on behalf of the unhoused, and how people in need of shelter are cared for and supported, especially in the winter months. Folks who have worked with me for years will learn I have an honorable discharge from the United States Marine Corps and express amazement, and I just say “you don’t know many Marines.” When people ask me “how can you still be a Republican and work on these issues” I reply “watch me.”

But I worry about our religious tradition, the Disciples of Christ, because I fear I hear it coming up again: “If we can get all the wrong thinking people out, we’ll be a proper church. If you aren’t interested in signing off of the right list of liberal causes, aren’t you going to be happier elsewhere? Because we sure will be.” Forgive me, but that’s the tone I hear all too often.

The Activists are just interested in cleaning up their mailing lists. The Idealists always have trouble imagining why anyone would feel differently than they do. And the Institutionalists are in disarray. There’s no real constituency for keeping conservatives of any sort in the fold.

All I can offer is this: you get rid of anyone who’s not fully committed to a progressive agenda, and I guarantee you this based on my reading of history — you’ll be divided about evenly over something else in about a generation. I wouldn’t even try to predict over what, just that the lower-case-p puritan impulse will keep dividing us into smaller and smaller communities, however constituted. Because it’s happened in literally every generation of our common life as Disciples of Christ, and in about every other generation it results in an overt, outright split.

I don’t want to tell progressives to soft pedal or downplay a single blessed thing, I just want to wave a warning flag (not an upside down U.S. flag, which is getting old on either end of the political spectrum, frankly) about the downsides of puritanism and uniformity. There is a sort of ideological pluralism, a quality of epistemic humility which I think our movement is actually uniquely situated to advance.

We are not only Campbell and Stone inspired theologically, I think we have a measure of Thoreauvian ideology. Henry of Walden Pond was pretty darn progressive in some ways, but his clarion call was “simplify, simplify.” In the same era, Campbell and Thoreau both tried to pare down religious practice and faith essentials to a bare minimum, to simplify as technology was (in the 1840s!) getting complicated and a bit overwhelming. So when challenged to add barriers to Christian fellowship and polity, Alexander Campbell in 1837, in response to a question about who really could be considered a Christian, offered this minimalist outline: “But who is a Christian? I answer, Everyone that believes in his heart that Jesus of Nazareth is the Messiah, the Son of God; repents of his sins, and obeys him in all things according to his measure of knowledge of his will.”

Today we would challenge his use of pronouns, and debate at length what “repents” means, but in his day, eight years before Thoreau moved out to Walden Pond, Campbell was stripping layers of gold leaf and chrome and bells and whistles down to a shocking minimum of religious ornamentation. Not a Quaker minimum, but he appreciated where the Religious Society of Friends was heading. We might want to expand even what obeying God means in a more ecumenical and even interfaith context, and our separated Restoration Movement siblings would throw up their hands in dismay, but the point remains: the Disciples of Christ religious tradition is rooted in a spare and lean minimalism which is portable and expansive, and that’s where even conservative Disciples want to be. Trust me. A simple table open to all, used as often as we preach and maybe even more so, as a sign and act of community which brings healing into a broken world.

Contrariwise, if we define ourselves on political unanimity, I will assert as a pragmatic historian that it will not last, because it never has. Republicans used to be for equality and in much of the country, Democrats for white supremacy. Then it changed. Many of my Republican friends have left the party; my own fellow party leaders suggested it was time for me to leave my role when it became clear I didn’t support the President. I vote for lots of Democrats, maybe even mostly, but I’m now still a Republican more out of sheer willful stubbornness than loyalty to family heritage. I haven’t changed, the party has. We could discuss what I think hasn’t changed; we might even disagree, which is fine. [Short “apologia pro vita sua”: my vision of government is still more federalist than federal, with states given wide latitude within a national set of norms imposed by Congress, but we don’t ask the federal government to micromanage every state and county and personal interaction, because history is messy. Part of my conservative opposition to Trump is because he wants to centralize and federalize all sorts of governmental roles under a strong Chief Executive, which ain’t conservative, no matter how often the Heritage Foundation tries to tell me it is. Anyhow. This carries over to my church life in that, for instance, I don’t want the General Commission on Ministry to directly dictate ordination standards for every region, EVEN when I agree with them and disagree with some regions in how they do this. Local can be stupid, but those tensions or questions mostly need to be worked out in the local context that created the stupidity, not fixed from above by fiat. Enough of that.]

Among my fellow Disciples, I will admit to some bemusement over feeling as if in my youth I was in the middle, a moderate in most things, and now I’m on the ragged edge of the right. Huh. Maybe that’s inevitable over time. I should study that. But I also know there’s a fair number of other clergy, let alone church folk, who are on this same margin with me. I think the religious tradition I’ve spent my life in would be lesser without folks like us, but I’d think that, wouldn’t I?

Which is why I wanted to take a shot at explaining to hopefully willingly listening progressives, who are thinking we might be getting close to having a proper church without all those conservatives and yes, without Trump voters. It’s not an Institutionalist argument I’m making over our giving and support; it’s probably fair to say many of us long ago began to be more cautious about what we gave to which element of the Disciples of Christ common life. Those discussions took up far too much of my years as a parish minister, and I’m aware of the sidesteps and evasions used to be “in but not of” the work of the general church.

No, it’s not the numbers, of people or in giving, but it’s the different nature of the whole. I have some strong suspicions I might yet work out by way of further writing (and Loren Richmond thinks this is long already!), about why the independent Christian Churches and Churches of Christ couldn’t be kept within a certain relationship with the cooperative and yes, more liberal or progressive fellowship of which I am proudly still a part. As with so much, it does have to do with money, but not in the ways you might think. Let’s just say Roger Ailes and Roger Stone, Willard Mohorter and Daniel Sommer, all have a great deal in common when it comes to wedge issues and the profitability of cultivating niche audiences with anxiety and fear, to sell subscriptions and bring in small dollar donations in large number. “Follow the money” can teach us a great deal, even in church life. Our splits, I believe, have had as much to do with our inarticulateness about money and faith as any actual theological debates.

That’s the problem, though. We are TERRIBLE in talking about money, about where it goes and what we expect it to do. We were terrible about it when we were more Institutionalist as Disciples of Christ, and we’re terrible in a different but related way in our current Idealist mode . . . and Activists are tightly focused on fiscals in ways that we can’t even begin to approximate, and shouldn’t try, but their uncanny focus leaves us vulnerable as a church to their pressures, because one of the aspects of our weakness around money is we totally don’t want to think it actually motivates anyone to do anything in the church. Such a sad, sad story to tell ourselves. It’s like saying children aren’t motivated by food, or young couples aren’t motivated by love. Money isn’t the only factor in church life by a long shot, but pretending it’s a minimal, negligible factor is sheer foolishness.

What I think we lost (along with a modest amount of cash) when we last split due to issues ostensibly over liberal vs. conservative views, was the counterbalance we can give to each other in discerning the will of God and the movement of the Holy Spirit in the Body of Christ. If there are two axes I’ve been harping on for the shape of the Christian Church defined as Institutionalist vs. Idealist, our X & Y axes, I think our loss of the more rural and pietistic element with the departure of the independent church took away our third dimension, our depth, which I’d define as a new axis along a tension between faith and practice (or praxis, if you wish). Epistemic Humility sounds too fancy, so maybe we call this third dimension plain old Belief. Believism would echo the structure of this metaphor I’m working on, but it’s straining under the load as it is. But the Belief we share in a hope that endures, in a God who listens, in Jesus as model and meaning and even as a Messiah, a saving person in the human story — that’s what anchors us and holds us together in any case. Belief as the central axis, which gives deeper dimension to our Institutionalism and Idealism.

If we lose more of that texture and depth, if we pivot even further towards a narrowly focused & tightly defined Activism as our primary dimension, I think we become both flatter and thinner, to where the fabric can tear under the slightest strain.

=+=+=+=

There’s an internal conversation, one in depth and breadth, we need to have about the extent of God’s love, yes, but also about the healthy boundaries of a functioning religious community. About what we believe as much as about what we are willing to do. Our GMP, Rev. Terri Hord Owens, has high hopes for The Church Narrative Project, and I see promise in what this approach tries to do. I also worry about who is included, and who excludes themselves (and why). I wish I had some simple solutions to propose in closing this extended reflection, I really do. The link to Terri’s project is https://disciples.org/churchnarrativeproject/

History also gives us some interesting examples to start with; the Lunenburg letter for one, the relationships between Alexander Campbell and Barton Stone, and between Thomas Campbell and Aylette Raines. We have a history of letting pretty extreme views live in tension . . . but tension implies connection, not to say covenant. The ties that bind allow that tension to exist, from which we can pluck melodies and music. The current trends in church life are to ask no questions for membership, to dispense with membership altogether, and even to eliminate most requirements to qualify for leadership . . . even as we expand in time and expense the expectations for ministerial status. Ministry is becoming highly defined, membership and community within our churches almost wholly individualistic. There’s a tension here that’s one sided, like a guitar string only attached at one end.

We are running short on experiences and content we share in common. There are those in our churches who thrive on Hallmark movies, and many who’ve never seen one. I was teaching a weeknight Bible study of some 50 people in 2019, and made an allusion to Iron Man and Captain America, caught myself, then asked “how many of you have seen a Marvel superhero movie?” One woman, about my age, proudly raised her hand. She was alone. Granted, this was a group almost entirely older than me, but still, I was taken aback.

There was a church event where I was presiding along with a seminary student, a second career person (not young, is my point) and the conclusion was for some reason not quite landing right, and I was moved to step up and launch into:

“Blest be the tie that binds

our hearts in Christian love;

the fellowship of kindred minds

is like to that above.”

As some readers will intuitively know, the congregation leapt to its feet and sang out in vigorous unison following my first five notes (“blest be-eee the ti-iii…”) after which I didn’t need to sing a single note. The rafters may not have shaken, but they resounded.

My seminary friend turned to me after the benediction, and said “What was that song? I’ve never heard it before.” If you didn’t grow up in church, I guess you wouldn’t.

Nowadays I do supply preaching, mostly around Disciples, UCC, American Baptist, and Presbyterian congregations. I always have to check which translation the church is using, and a) the standard according to the resident minister is always different, and b) more often they say “oh, everyone uses different translations, just use whatever.”

And I have been for years now teaching a Disciples of Christ history and polity course online, eight weeks of semi-asynchronous material intended for both commissioned ministers but also almost as many people with ordination in another tradition who are seeking standing with the Disciples, so we have anything from Ph.D.s and J.D.s and M.Div.s to folks who finished high school and have worked in their community for decades, now serving as minister for a couple dozen.

One thing that always comes as a surprise to the class members each eight weeks cycle — well, two things — is that every Disciples church does NOT have the same hymnal, and that you have to ask if a congregation’s Lord’s Prayer uses “trespasses,” “debts,” or “sins.” Again: Disciples don’t all use the same form? We don’t all sing from the same hymnal?

This is either a strength, or a weakness. I regularly get students who make the case for why they think it’s a weakness (and they usually grew up in a different church tradition). Some are clearly troubled that there’s not a set standard for them to follow. Let’s not even get started on whether communion is before the sermon, or at the end of the service, or if the bread and cup are taken together in the pews, or the bread as it’s passed but the cup in unison, or . . . seriously, this really amazes some people to learn the other twenty students don’t do it the way their church “has always done it.” Uniformity is comforting, reliable, easy to manage at least in some obvious ways.

I think our diversity — ALL of our diversity — is a strength. But there’s a lot of interest in uniformity. And I do wonder at what we’ve lost, when I sing a hymn at a nursing home, and even the long quiet, mostly non-verbal residents all lift their heads and with eyes closed sing along, some just moving their lips, but unequivocally knowing the words to “Amazing Grace” or “The Old Rugged Cross.” A generation will come which can’t be rallied by starting “Blest be the tie that binds…” or even by an a cappella “This is the day…”

Perhaps diversity has its limits. Individualism versus uniformity, autonomy versus covenant. I still read the 23rd Psalm in the King James Version at graveside services, but increasingly people aren’t having even graveside memorials. Cultural change is happening faster than we are able to adapt to, theologically or ecclesiologically. We have to maintain the dialogue, the narrative, the conversations around belief and practice.

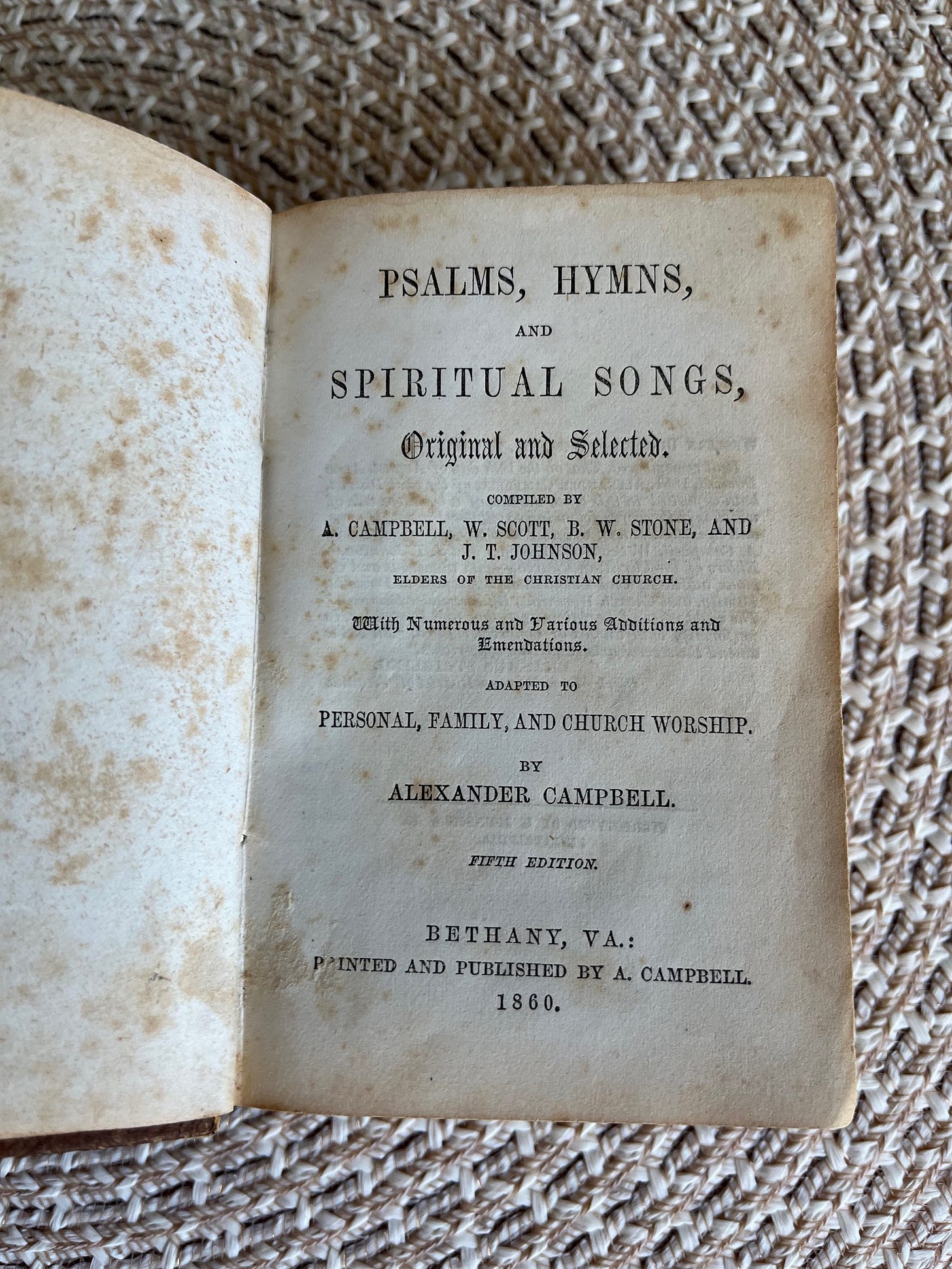

Out of my family history, I own a number of hymnals, and an edition of Alexander Campbell’s “Christian Hymnbook” of 1860, whose proceeds built the early Disciples of Christ, as he turned the copyright over to the American Christian Missionary Society. My paternal great-grandfather’s hymnal of 1873, and my maternal great-grandmother’s hymnal of the 1890s, given her by her own father.

Campbell’s hymnal has almost 600 hymns in it: there are perhaps half a dozen anyone, even someone grown up in church and getting old like me, would recognize. “Hark the Herald Angels” is in there, and a few others like “Amazing Grace.” The other two are newer, and there are a few more in each one that ring at least a faint bell for me, but mostly they are hymns largely lost to the church of today. And of course, many churches are getting rid of hymnals altogether, for the collection of downloads on their screens that constitute the repertoire of that congregation’s musical context.

History is going to be one of the few things we can hold in common going into an uncertain future. The history of how we came together, and the history of the things that drove us apart. The history of the things that unite us which we take for granted, and the history of what we’ve tended to keep hidden in the closet, and how we come to face those past choices which shape us still. Hymnody or instrumentation isn’t going to unite us: a melodeon would sound quaint to modern ears, and the instruments which church factions fought over in the 1890s were as likely to be trombones and clarinets as they were full-blown pipe organs. The King James Version of the Bible isn’t going to bind us together; today, using the RSV is considered odd & backwards, when in my youth it was a standard the progressive carried into battle against conservatives.

Only history is going to stay with us, both the history we know, and the history which is embodied in our collective set of choices and options whose roots, to be fair, few know. But those historic roots and connections over time exist, and are part of the tension between past and present which is why change is so hard. Someone is pulling back on the other end, and as Faulkner famously said “the past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past.”

Our very definitions as a tradition, a church body, even as a denomination, are tied to that history which lives in us. Why do we have a general tendency to avoid saying “denomination”? You don’t have to know why to feel that pull. Why is sacramental language, including about sacraments, an awkward fit among Disciples of Christ? As I tell students all the time, sure, you can use that language. But you should know why for many the term “altar” provokes a wince over “table,” or where that odd term “ordinances” comes from. We are in an ongoing conversation with our past even as we struggle to talk to each other, live and embodied.

That’s why we need regional and general assemblies. And I believe they will go better the more we have dialogue and conversation within our congregations around what we believe, where those beliefs come from out of our history, and what we should do about them. Beliefs as a basis for conversation take us to a very different place than when we debate issues or argue about causes. Beliefs draw on different wells of experience and information and understanding.

I believe in happy endings. Granted, experience doesn’t support that belief very well. But my religious tradition, my family narratives, and a theological understanding that is ready to be challenged leads me to smile and say “yes, I have a reason for the hope that is in me…” and to respond to those who doubt me with gentleness and respect (I Peter 3:15). Gentleness and respect as key to dialogue: who knew?

Hallmark movies aren’t realistic. I know that. Denominations have a dim future in the world as it is heading. I see that. What our history as Disciples of Christ gives me, though, is a template for holding onto, and even holding up, a hope in uncertain times which can shine and encourage others, even as it is a light onto my own path. Our problems won’t be solved in two hours run time, or by any one program out of the OGMP, but in the light of history they can give us a model for being the kind of community I believe people are looking for.

“And God is able to provide you with every blessing in abundance, so that by always having enough of everything, you may share abundantly in every good work.”

~ II Corinthians 9:8

Jeff,

Thank you for these thoughtful reflections! This was my first GA to attend, and I appreciate your insights into where we've been and where we're headed as Disciples.

My jaw briefly hit the floor when you brought up the Klan in this post. Oddly enough, I also found myself browsing Newspapers dot com recently for info on our church's Christian Endeavor chapter (FCC of Hot Springs, AR). I learned more than I expected, to say the least!

One of the articles I found detailed a troubling event in our church's history. On Sunday afternoon of 2/15/1923, at the halfway point of a revival at FCC Hot Springs, Rev. Harry Knowles, who was then the minister at FCC Little Rock, gave a speech about the Klan. His title was what we would call "clickbait" today. I don't have the piece in front of me, but it was something along the lines of, "How to Destroy the Ku Klux Klan." Rev. Knowles' railed against the disintegration of family values and morals in quite contemporary-sounding ways. Then it got a LOT worse. Here's a quote I pulled from near the end of the newspaper article:

"Declaring that the time was at hand when the people of America must rise in their might and put down the conditions that threaten the very heart of the republic, Dr. Knowles declared the Ku Klux Klan was the only organization at this time in the country wherein all Protestants, whether church members or not, but believers in the tenets of the Christian religions, could unite as one mighty force."

Not exactly the unity Jesus had in mind in John 17....

Doing a little more research, just 6 months before this speech a Black man had been lynched just a few blocks from the church for allegedly killing a man who was (again, allegedly) a Klan member.

It's sad how commonplace such stories are. I know it's tangential to your post, but I thought it would make a good corollary to some of the finer details of your discussion.

Thanks for the many hours of work you put into these posts.