"If it is a hoax, it is ingenius [sic], and a first class deception which involves whole communities, and especially educated, and some scientific men…

It appears to me to be quite possible and even probable that the stone may have been expressly prepared, inscribed and deposited by some facetious fellow to furnish sport for him at public expense…"

~ W.D. Bickham, Cincinnati Daily Commercial, 10 July 1860

Before we return to June 29, 1860 in Newark, Ohio, and the discovery by David Wyrick of the first of the Newark Holy Stones, there’s some questions we probably should answer first.

Questions of sequence, and perspective, plague any attempt to make sense of the many and various narratives that have built up around these objects. Even contemporary accounts in newspaper articles and correspondence have to be closely parsed as to timing.

For instance, Charles Whittlesey gives us some very detailed information about the events of that day in multiple published accounts starting in 1860: but the detail increases when he writes about them in 1872, after a dozen years, following his own service in the Civil War, and after Wyrick’s death in 1864. And he changes his position on what he thinks about the history and authenticity of them, from his earliest account we have which he wrote on July 2, published in a Cleveland paper July 14th. There he largely accepts them as ancient and authentic artifacts. By 1865 he considers them to be relatively different in age, but both authentic; following the war in 1866 there’s an account where the hedging on both is obvious, and by 1872 he’s writing for general publication under the heading “Archaeological frauds. Inscriptions attributed to the Mound Builders – three remarkable forgeries” which most definitely includes the Newark Holy Stones.

Meanwhile, closer to the events as they happened, we have newspaper accounts, often anonymous (bylines were rare in journalism in that era) but sometimes with parts of letters from parties involved in the discovery and study of the artifacts. One we used in closing the last chapter:

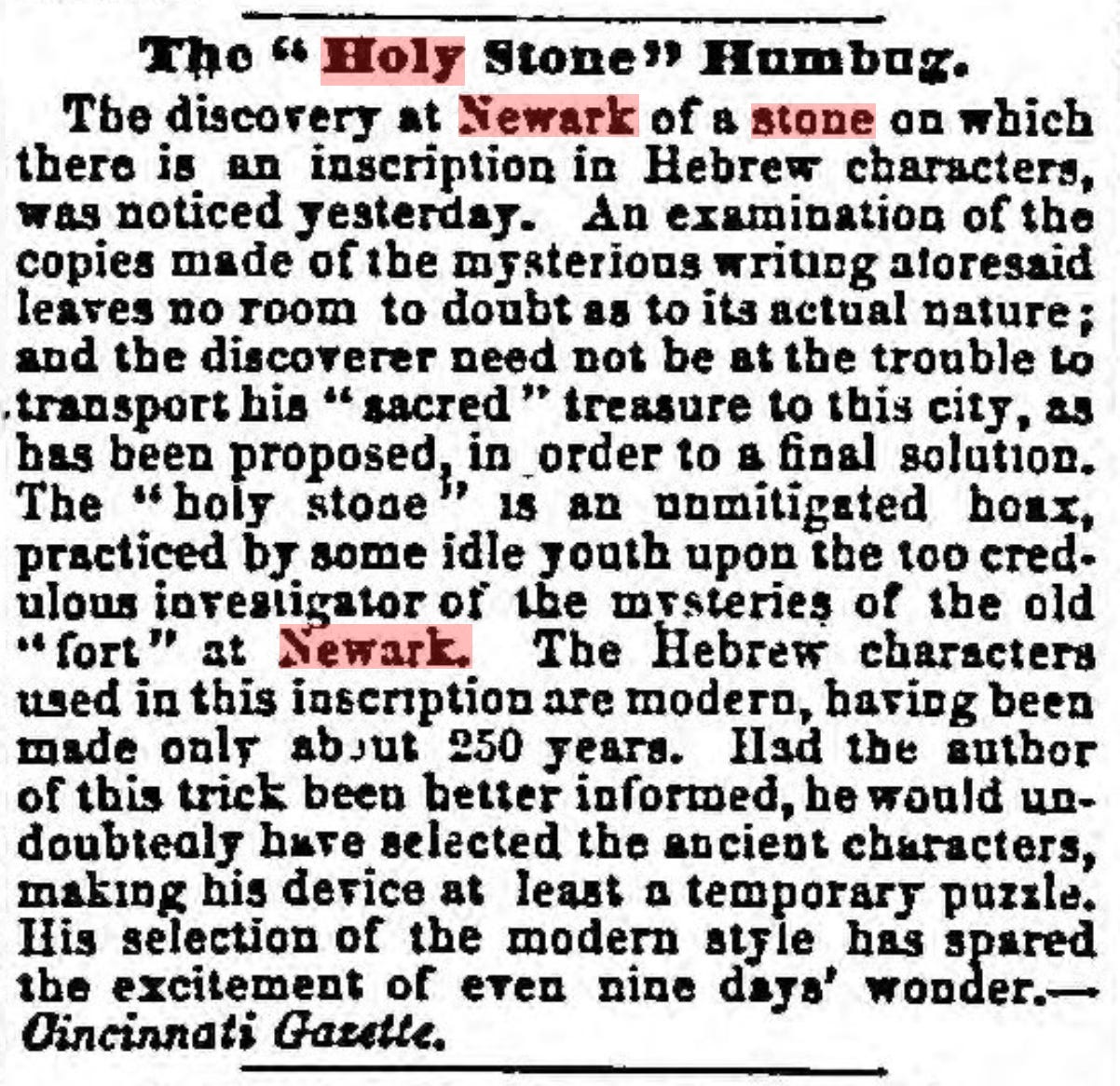

This is the second Cincinnati newspaper article we find on the Newark Holy Stone (there being only one at this point), and the word “Humbug” is already being used in the headline. We have some fairly detailed coverage on July 9 and 10 in the Cincinnati Daily Commercial, under the heading “Letter from Newark” edited by W.D. Bickham.

William Denison Bickham is one of the many sideline figures in this account who represent a serious temptation to digression. Educated at Bethany College, a prospector in the California gold fields, rose quickly to the rank of Major under General Rosecrans in the Civil War, and in and out of it all, a newspaper correspondent and ultimately editor. And he worked across Cincinnati and Dayton at a variety of papers in an era when those cities each had half a dozen major print publications apiece, not counting some of the more narrowly focused but influential papers in German language, or for specific businesses.

W.D. Bickham, in 1860 at this time, is city editor for the Cincinnati Commercial under Murat Halstead’s general editorship, which had a Daily edition, and a more comprehensive Sunday Commercial. Someone is his correspondent in Newark, but it is not clear who that is.

“An unmitigated hoax, practiced by some idle youth upon the too credulous investigator…”

At this well-nigh earliest public report, dated from days after the discovery, we have a fairly candid statement of the case. There’s a certain florid character to the adjectives used — unmitigated, idle, credulous — which are actually fairly typical of reportage of that time and place. But the basic elements of a hoax or fabrication, done by an unknown party to fool a likely dupe, are the essence of where we stand today, in 2025.

Jumping more fully into the present day, there’s a challenge offered up by some who look into the overall question of the Newark Holy Stones, which is “why are you so certain these are forgeries?” We’ve come to call it “the Alrutz Proviso,” for the late Denison University professor of biology who became in 1980 a champion for the possible authenticity of the artifacts.

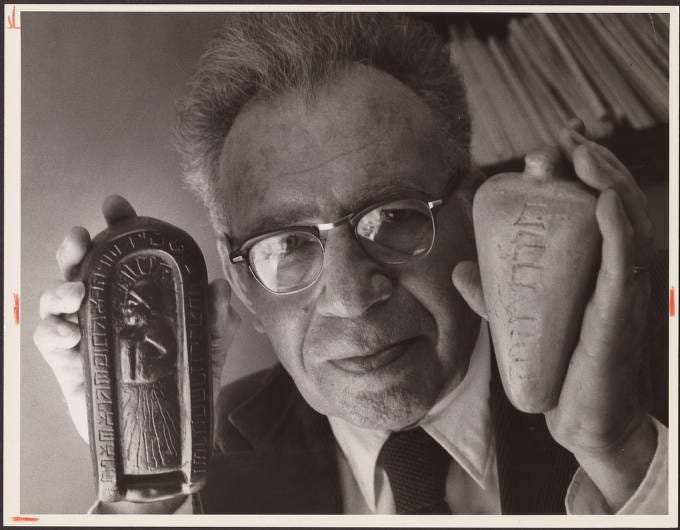

Robert Alrutz (1921-1997) is a still legendary figure on the Denison campus, founder of “The Homestead” as an agriculturally based, self-reliant democratic community where students live as well as learn, and creator of the Denison University Biological Reserve in 1969. An entomologist from his doctoral work at the University of Illinois on mosquitoes, he was also a parasitologist, and came to be considered the leading expert on the dragonflies of Ohio. After being exposed to the work of Rachel Carson, he introduced Denison to the concepts of ecology, and environmental studies, which he helped create as a program and major on campus.

He was also a deeply religious man, who believed in what’s called “Young Earth Creationism” and was skeptical about evolution. As you can tell, Bob Alrutz was and is hard to pigeonhole.

Brad Lepper and I can also testify that Bob enjoyed a good argument, and gave ground rarely once he had staked out a position. By 1980, he had become convinced that the story of the Newark Holy Stones was, to use the title of his paper published that year in the “Journal of the Scientific Laboratories, Denison University” volume 57, “The History of an Archaeological Tragedy.”

In this 50 page essay, which was later separately published, Bob discusses five Newark Holy Stones. It’s worth noting that even in the seemingly simple question of “how many Holy Stones are we talking about here?” there is room for diversity of opinion. There are five objects found between 1860 and 1867 which have Hebrew inscriptions on them, even though most discussions on this subject focus on just the first two.

However, the second one (which we have yet to meet) comes in a carefully crafted stone box of two parts, and in the course of excavation a stone cup or bowl is found close by, and two octagonal plummets, or plumb-bobs, made of stone as well. Depending on how you count the box halves, we are talking about either nine or even ten stone artifacts in total.

The stone box for the second Holy Stone, or the Decalogue Stone as it’s known, is important if only for “the Alrutz Proviso.” Bob would point to the very detailed craftsmanship of his stone container for the more decorated Decalogue Stone, cradling the object and carefully made to fit together, and in high excitement proclaim “I ask you: if this is a fraud, why would someone go to such trouble just to create a box to put it in? Why?”

That’s the question, and it’s fair for Bob to have asked it. The Newark Holy Stones aren’t a casual prank or an idle jest. Someone DID put a great deal of work into them, and to explain them requires we have an answer to “the Alrutz Proviso.”

But it may be necessary before we go further to give a simple answer to the basic question: why do we start from the assumption they’re fake artifacts, a “scientific forgery” to be more formal about it? Why not begin with the idea that they’re what they appear to be, a sign of a Hebrew speaking presence in Ohio before the arrival of European settlers or American historians?

Bickham’s terse dismissal gets at the heart of why so many of us begin with “they’re fakes.” From the outset, at least some observers noted an obvious problem with the Keystone. The Hebrew characters are, in fact, modern “typeface” Hebrew letters. The serifs, the details at the beginnings and endings of strokes to form each letter, are unambiguously identical to how the letters look in a printed modern Hebrew Bible. Imagine someone tells you they had a document that was contemporary with the Declaration of Independence; they say they found it in a bundle of parchment from the late 1700s, and it’s handed to you so you can feel the brittle crisp texture of aged parchment. You lift it up, and look, and the wording may sound Jeffersonian, but you notice: it’s printed in Comic Sans. Microsoft came out with the font Comic Sans in 1994. No one working a printing press to publish documents in the 1770s printed with letters that even remotely looked like Comic Sans back then. You’d say “it’s a fake.”

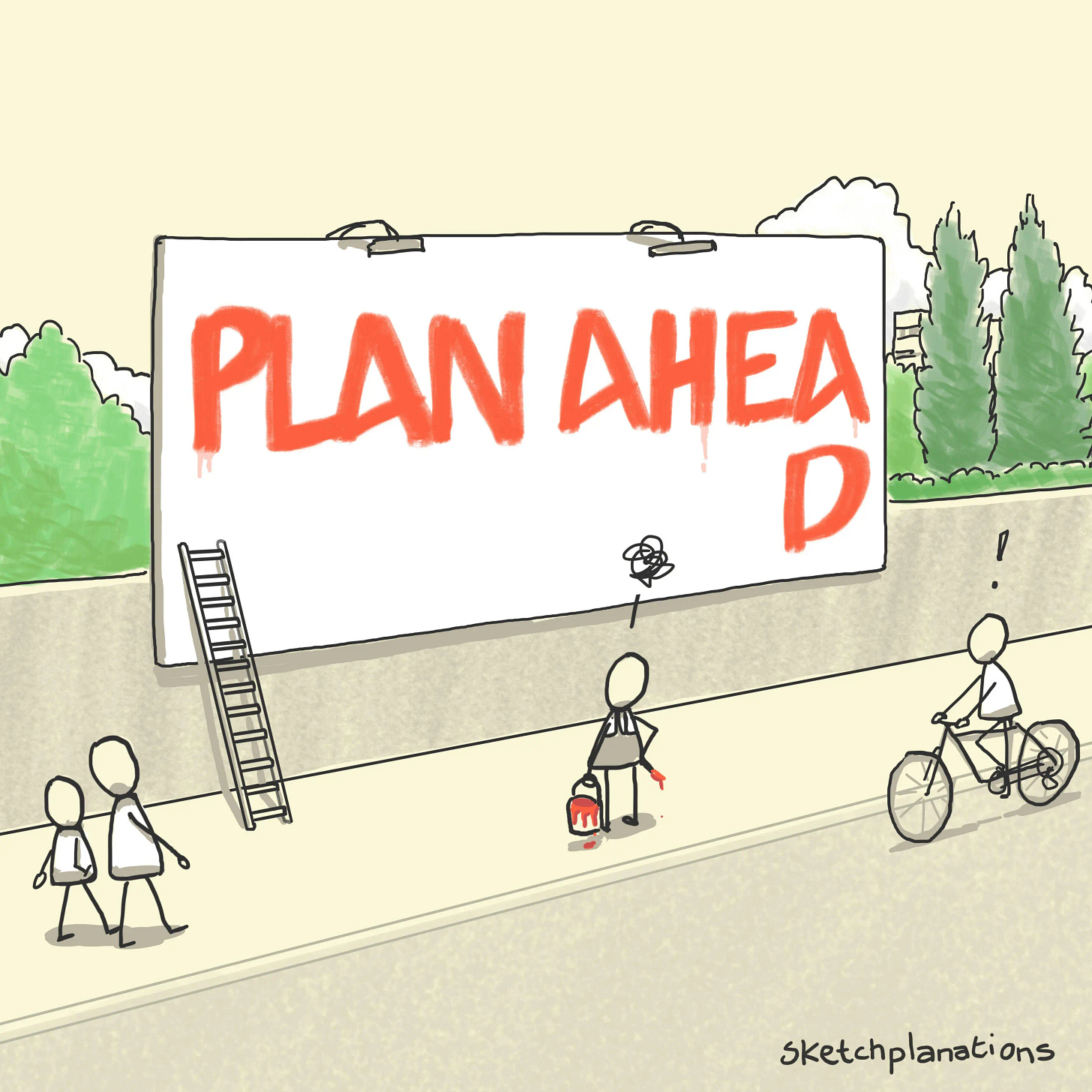

In fact, if you pick up the Keystone and read the Hebrew phrases carved into the four faces of this wedge-shaped object (see the previous post for images of all four sides), you wouldn’t need a working knowledge of Hebrew to notice quickly something not right. Hebrew is written from right to left. Each phrase carved on the Keystone starts with a nice margin on the . . . left, then you can see how the letters start to crowd as they approach the right. It’s like the old “Plan Ahead” visual joke:

The carver gets better, but never quite manages to obscure the obvious reality that they are carving the inscriptions on left to right, while they read right to left.

There are two other issues that come up in most analyses of the Keystone: that it was found in a rather shallow context that didn’t require great age for deposition, and almost immediately on Wyrick’s return to town, comments were made about how the shape resembled Masonic ritual objects, such as in the Royal Arch Masonry fellowship, which may be the source of the name associated with it ever since, the Keystone. Whether keystone of an arch, or as a plumb-bob due to the knob on top that seems designed for attaching a cord, which allows a builder to determine straight lines and perpendicular walls, the general consensus even in Newark began with an assumption that the Keystone was not old, but perhaps a piece of lost Masonic regalia that just found its way into a pit on the edge of town.

Interestingly, many of the more current supporters of the Newark Holy Stones as evidence of a Hebrew presence in central Ohio some two thousand years ago will fairly quickly concede the Keystone isn’t ancient. The letter shapes, the inscription pattern left to right, and the clear marks of a narrow scribing tool made of high quality metal scratching out the serifs of the modern Hebrew, all make their own case for contemporary manufacture in or just before June of 1860.

Why it was there for David Wyrick to find is a question no one really wants to touch. It’s just tossed off as “no, the Keystone isn’t really an ancient artifact, but the Decalogue Stone is, and that’s what I want to talk about.”

Bob Alrutz would often accept dismissal of the Keystone in conversation, but he would circle back to it, asking “why couldn’t it have been…” Still, no one wants to base their argument for a Hebrew speaking presence in North America on it.

The Decalogue Stone has, as the name implies, the Ten Commandments, or “Decalogue” carved on its surfaces. As we’ll describe in more detail later, the finding of the Decalogue Stone four months later neatly answers the main objections to the Keystone’s antiquity. It is found, if not deeply buried, in a context which could or should have meant it was interred beneath what had been a forty foot high stone mound, and deep into clay beneath it, under a log coffin with materials in and around it closely defined with the culture we would come to describe archaeologically as “the Hopewell culture.” The letters on the Decalogue Stone are not in typeface Hebrew, but a near-cryptic squared off version of the Hebrew alphabet, hinting at a history more associated with stone carving than printing or writing on paper. And there’s nothing obviously Masonic about it, from the figure of Moses on the front to the shape of it all around. This object feels older, or at least was made to seem so.

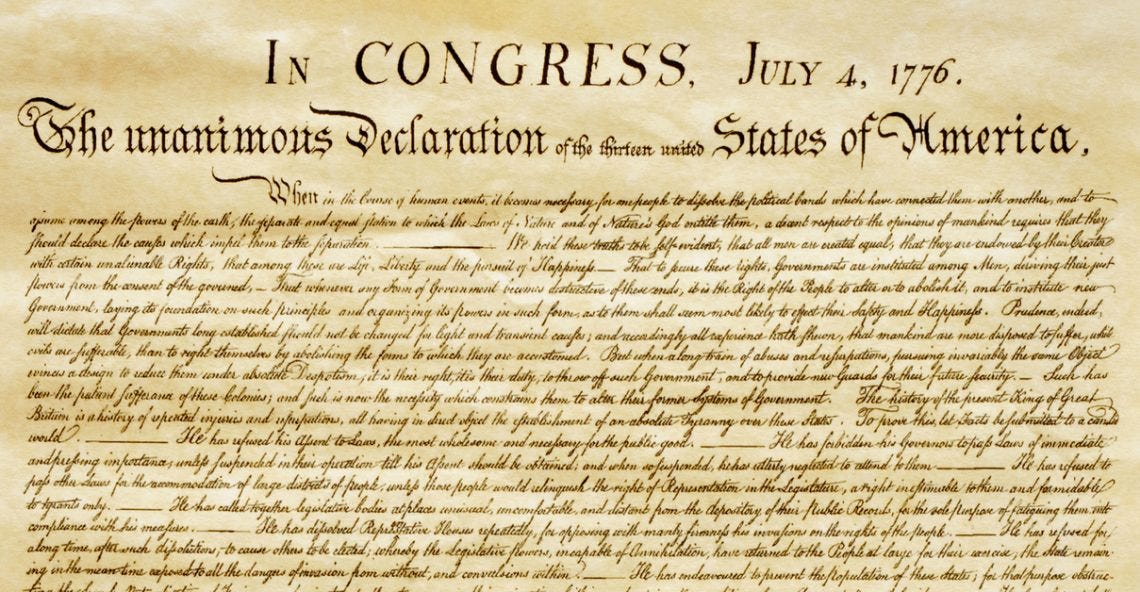

Again, to preview a more detailed argument to come, the big problem with the Decalogue Stone is that the “square Hebrew” is all too obviously transposed from a modern Hebrew text into a made-up alphabet of primitively shaped letters. Let’s go back to that document from the 1770s that might be connected to the Declaration of Independence, but not in Comic Sans.

Think about that first line, in a standard facsimile of the original handwritten one Nicolas Cage steals in “National Treasure”: “When in the course of human events, it becomes necefsary for one people to difsolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to afsume among the powers of the earth, the feparate and equal ftation to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they fhould declare the caufes which impel them to the feparation.”

Standard handwriting and print of the 1770s recognized two different letter-S shapes. What we think of as standard lower-case “s” was mostly used as a terminal form, the “s” used at the end of a word or as the second form if there were two letters “s” in a row. In contrast to the terminal form, the standard “s” in Revolutionary times looked more like a lower-case letter “f.” So you have “ftation” for station, and in doubled s words like “necefsary” or “difsolve” or “afsume” you have two different shapes or letter forms. (Just to complicate it, “course” looked like we’d expect because the e is silent, so it ends with s audibly, and hence the f-form of s isn’t used, because it’s effectively terminal.)

On the Decalogue Stone, there is a pattern of errors in the letters which makes no sense in the Hebrew of the Decalogue alphabet . . . but perfectly matches what would happen if someone who didn’t know Hebrew was transposing from modern Hebrew with its terminal forms into a different set of Hebrew letter shapes. Like my example of the first line of the Declaration of Independence above, I’m putting “f” in for effect where I actually know those are actually an archaic way of writing “s” at times. But if I didn’t know that . . .

There are actually two different sets of errors in the Decalogue Stone’s inscription which point to the basis of it being in modern Hebrew. That further suggests that you have someone who came up with the “square Hebrew” of the Decalogue alphabet, who had to get someone else to carve the object and that person didn’t even know basic Hebrew.

Add in the facts that both Hebrew inscribed stones were found by David Wyrick, within months of each other, with the second perfectly answering the objections raised to the first, and you have a working basis for why most scholars and investigators have concluded these were created objects, crafted with a purpose, and planted to be discovered by an unsuspecting party who would then publicize them widely. You could also add the odd fact that both the Keystone and Decalogue Stone are essentially the same dimensions, in width, thickness, and height, the latter stone having a sort of handle on one end.

It’s enough to make you think the same person made both.

The additional Holy Stones are found in the years immediately after the Civil War, and will not hold up for reasons we’ll get to in due time, but suffice it to say they aren’t plausible and few today refer to the Cooper Stone, the Inscribed Head, or the Bradner Stone, for good reason. The main debates around the Newark Holy Stones have to do with the Keystone and the Decalogue Stone, and even if you dismiss the Keystone as a mystery, but not a fraud, the Decalogue Stone simply doesn’t stand up to any sort of close scrutiny. And frankly, I think they both stand or fall together; as you can tell, I see them as definitely fallen artifacts. Frauds, hoaxes, forgeries.

Which leaves us with “the Alrutz Proviso.” As Bob said, that stone box is a challenge. It is a huge amount of extra effort, to no particular end in terms of supporting the argument that these artifacts indicate a Hebrew presence in ancient North America. The stone bowl, too is a bit of extra effort that contributes little (the two octagonal plummets are lost, and may have been actual Native American artifacts themselves, planted with the Decalogue Stone or even found in the fill from the legitimate ancient materials just above).

Bob was right about one thing: this is all too much work to have been a prank. Whoever created and planted for discovery these two objects (plus a two-piece stone box, a bowl, and two plummets) had a reason to do so, an intention that drove them. That’s a big part of why you have this extended treatment before you — the interesting question around the Newark Holy Stones isn’t whether they’re proof that Hebrew speakers were in Ohio around two thousand years ago, because the surface evidence is strong that they aren’t that. The interesting question is as Bob asked, if for somewhat different reasons, “Why would someone put so much effort into making these objects?” We may not be able to answer definitively the question of WHO made them, but there is a strong case to be made for WHY they were made . . . one that might even justify the obvious effort that went into the making of them.

====

Part 1- https://knapsack.substack.com/p/june-1860

Part 2 - https://knapsack.substack.com/p/june-29-1860

Part 3 - https://knapsack.substack.com/p/i-wish-to-god-some-one-else-had-found